During my tenure as Editor of Realskiers.com, one of the benefits of membership has been a long-form ski review, accompanied by test scores complied by our small volunteer army of testers. Long-form reviews are still a principal component of the Realskiers’ membership bundle of benefits, but the data will no longer be a part of the presentation for the simple reason the paucity of entries results in data that is more detrimental than beneficial.

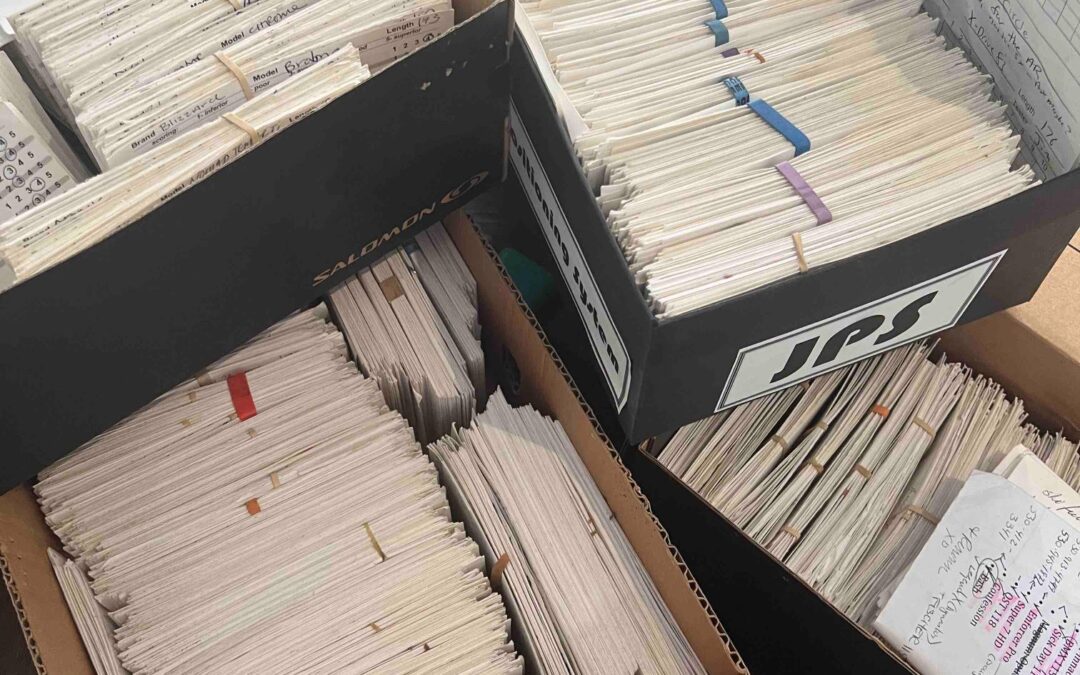

Now for the not so simple reasons. The Realskiers Test Team has always been primarily comprised of shop personnel, from owners down to seasonal salespeople. Once upon a time, this produced hundreds of what were then paper test cards, often with 20 or more entries per model. The test cards are digital now, which creates its own set of challenges – pencils don’t suddenly go haywire for no apparent reason, but apps do – but the much greater problem is that shops are already understaffed; sending a manager and a coterie of testers off to test skis for 2-3 days is not in the cards.

There are also fewer demo events to attend, in part because suppliers are imposing early order deadlines, drastically shrinking the window between the first appearance of demo skis and the drop-dead date for submitting an order. And that’s assuming the weather cooperates, but last year at Mammoth, it was in no mood to trifle. The event lasted all of one day before being weathered-out.

With fewer testers getting fewer opportunities to test, getting any kind of feedback has become a season-long chase. The end results are wildly imbalanced, and so few in number that if you start tossing out anomalies, pretty soon you don’t have many numbers to work with. It seems apparent to this ski test maven – I’ve been at this game since the winter of 1986/87 – that the numbers can’t be trusted. Nor is there some formula by which they can be “fixed.” When numbers beg for fixing, you know their value to the end user is damaged beyond repair.

To put the present circumstances in perspective, allow me to cite my friend Bob Lefsetz – whose copious output you can read at (https://www.lefsetz.com/), a prolific social commentator – and passionate skier – who happens to be the most influential blogger in the contemporary music omniverse, on the frailties of data, to wit: “Not all data is created equal.” To which he trenchantly adds, “But even worse, all data analysis is not created equally.” Lefsetz is pontificating about today’s political punditry, but his observations pertain to any realm where numbers posture as the distillate of reality.

Despite its air of substance, data can distort reality even before it’s entered. Any tests that use a 5-point scale will always end up cramming nearly the entire field into a de facto 3-point range, a phenomenon I first observed when reviewing skis for Snow Country Magazine. When I started with a 5-point scale, the better testers were often putting an “X” on the line between enumerated boxes, to create some separation in a field that might extend to 20 models. I realized then that if I really wanted to identify the best in any category – in a market with far more brands than we have today – I needed a 10-point scale. This allowed me to then rank the results in order of finish, helping drive consumer interest in our start-up publication.

The reason I published our detailed test results then and have done likewise for Realskiers subscribers to the present day, is that people place a disproportionate trust in data, as if the numbers being published weren’t made by the same people who wrote the text. My point is that numbers aren’t inherently truthful, despite being composed of numerals instead of letters.

From my perspective, the biggest issue with data and its interpretation is that it’s an arid way to describe the ski experience. It potentially still has some value when comparing one ski to another, but whether a ski earned a 3.7 versus a 4.0 for edge grip still doesn’t tell you much about how it feels to ski on it. Even this limited attribute goes out the window when one ski result has 3 entries behind it and another has 30. There’s no way to equalize the imbalance in the number of entries, period. Not to mention that treating all results equally is based on the generous assumption that all skiers are equally qualified to submit entries in the first place.

It’s reached the point that numbers are so problematic they are as likely to distort as to describe a ski’s performance envelope. Testing skis on snow is still a valid exercise, particularly when asking a specific question about a specific feature, such as a change to a single core component. For testing to have any validity beyond this limited scope, there has to some rationale to the composition of the test team, just as there has to be an educated, common understanding of each test criterion. These requirements beg for a measure of control over the data collection process, control that I can’t exert from where I sit.

One unequivocal benefit to sharing ski test data with my Dear Readers: doing so provided a system for ordering each category’s reviews based on merit rather than the alphabet. Despite the absence of published data, I will continue to divide each genre into Power and Finesse camps and rank them according to my estimate of how they measure up against their peers.

If there’s a redeeming aspect to the demise of dependable data, it’s that its absence places the emphasis of any review squarely on the narrative, where it has always belonged. The qualities that real skiers seek in a new ski can’t be conveyed by numbers, and aren’t so easily fashioned into readable prose, either, as a romp through almost any ski website will sadly make plain.

The goal of any ski review is, or ought to be, to help the prospective ski buyer sort through a maze of options and end up on the best choice for him or her. The average price for a quality ski/binding set-up will easily exceed $1,000 this season, so it pays to do a little research. There is no better place on earth to do this research than Realskiers.com, if for no other reason than our site has one asset no other can simulate, imitate or copy: me. One of the privileges of membership is that I answer all queries personally, and I stay with you until we get your problem solved.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Related Articles

Road Tripping

Among the many dissatisfactions of this most unusual season is that travel beyond one’s local environs has been roundly discouraged. Don’t get me wrong: I’m grateful down to my socks that we’re allowed to ski locally, and my version of same is pretty sweet. Pardon the plug, but between Alpine Meadows, Squaw Valley and Mt. Rose I have a smorgasbord of savory choices.

But skiing close to home and skiing on the road are two different beasts. Nothing is the same, really, and therein lies a great deal of the road trip’s charms.

To shed light on my premise, allow me to pull back the veil on my favorite away game, an annual pilgrimage to Little Cottonwood Canyon. By the end of this brief travelogue you will probably hate me, so please fill your vessel of good will to the rim before proceeding.

It’s About Nothing

In the last week of January,2009 I was able to spend a few days skiing in Little Cottonwood Canyon, which is always cathartic for my ravaged soul. The conditions were all over the map, the mountains having experienced a long, hot spell followed by rain, grapple, wet snow and finally dry snow driven by winds that could flense an adult walrus in a few minutes. Couldn’t have been better.

I had been preparing for the trip for weeks, psychologically. Two back surgeries the previous winter had reduced my training regimen from semi-annual to non-existent. Scheduling conflicts such as work kept me from visiting the areas that abound at home near Lake Tahoe, so I had zero ski days on a body with more fat on it than a French duck. I had as much chance of surviving Snowbird and Alta as a rib roast in a piranha tank.

Fortunately, the Lord is merciful, anti-inflammatory drugs are powerful and there are techniques that allow one to block out pain. There are also many wonderful people in this world with which to ski, kind people who stand quietly by, pretending to be in awe of Nature, while my chest heaves so violently in its futile quest for oxygen that tiny lung particles break lose and make for the exits. One such person is Guru Dave Powers, a man whose passion for the sport hasn’t diminished after thousands of days of riding gravity down the infinitely variable slopes and crannies of Snowbird. The Goo knows this hill, and in knowing it well knows so much more.

The Making of a Skier, Chapter XII: Putting Words into the Mouth of God & Other Mid-Life Adventures

When I was cut adrift by Head on June 13, 2001, my once glowing prospects dimmed considerably. The date is etched in memory because I hosted a small soirée that evening in honor of my darling wife’s 50th birthday. One of the attendees was Paul Hochman, who would play several roles in my life as I wandered in the wilderness of unemployment during what were supposed to be my peak earning years.

During the gaping hole in my career that spanned 2001-2011, I would eventually spend every cent of my inheritance, plus most of what I’d saved from earlier bouts with gainful employment, just keeping the household afloat. Despite a river of red ink, my resume would suggest that I was not only commercially active during this epoch, but had my hand in all sorts of ventures.