Dear Readers:

I subscribe to exactly one blogger, Bob Lefsetz, whose passion is the music scene, but his restless mind and flowing prose are by no means confined to this subject. Lefsetz’s second love is skiing, a topic to which he often strays in winter months. In a blog post dated November 28 – he frequently posts several times a week – he wrote a burst of sentences that caught my eye:

“And Killington got hit. But I know the further south you go, you get rain, but at Bromley, my home mountain, where I grew up, they literally got twenty-four inches, TWO FEET! This is so rare. It hasn’t happened in November since 1968.”

Lefsetz had dropped his paddle in deep waters, stirring up eddies of memory that were undisturbed for decades. I had to let out the sudden rush of recall lest it burst through my forehead, so I jotted down this mind belch and sent it off to Bob (in lieu of expensive therapy).

I grew up on Big Bromley – my mom designed a little cabin (expanded thrice under Hogen ownership) in Peru, right across from the Deer Crossing sign on Route 11. My godfather, Bill Parish, ran Johnny Seesaw’s, which, as you may recall, you could ski to off the Pushover trail. (Parish, with his brother-in-law Lew Deschweinitz, were the first importers of Raichle and Dynastar.)

My parents bought the land from Mr. Lord (a scandalous $1,000/acre) of Lord’s Prayer fame. Neighbors were Serge and Patti Gagarin, he an erstwhile Russian prince (and an engineer at Sikorsky), she a socialite; the Thornes, whose son married Tricia Nixon; Amory Bradford, V.P. at the NYT, whose first wife was a Rothschild. Also among of the cocktail party regulars were Commander Whitehead of Schweppes fame and his regal Welch wife. And Bob Myhrum, who directed Sesame Street for 13 years, then lost all his savings to a fraudulent accountant.

When I was 7 I caught my first trout (or fish of any kind), in the little stream that meandered through the cow pasture across the street from our house. I learned to play tennis by hitting the backboard on the red slate clay court at Seesaw’s. Both my parents are buried in the small cemetery by the schoolhouse, near a pasture where my mother used to ride her horse, her favorite thing in life.

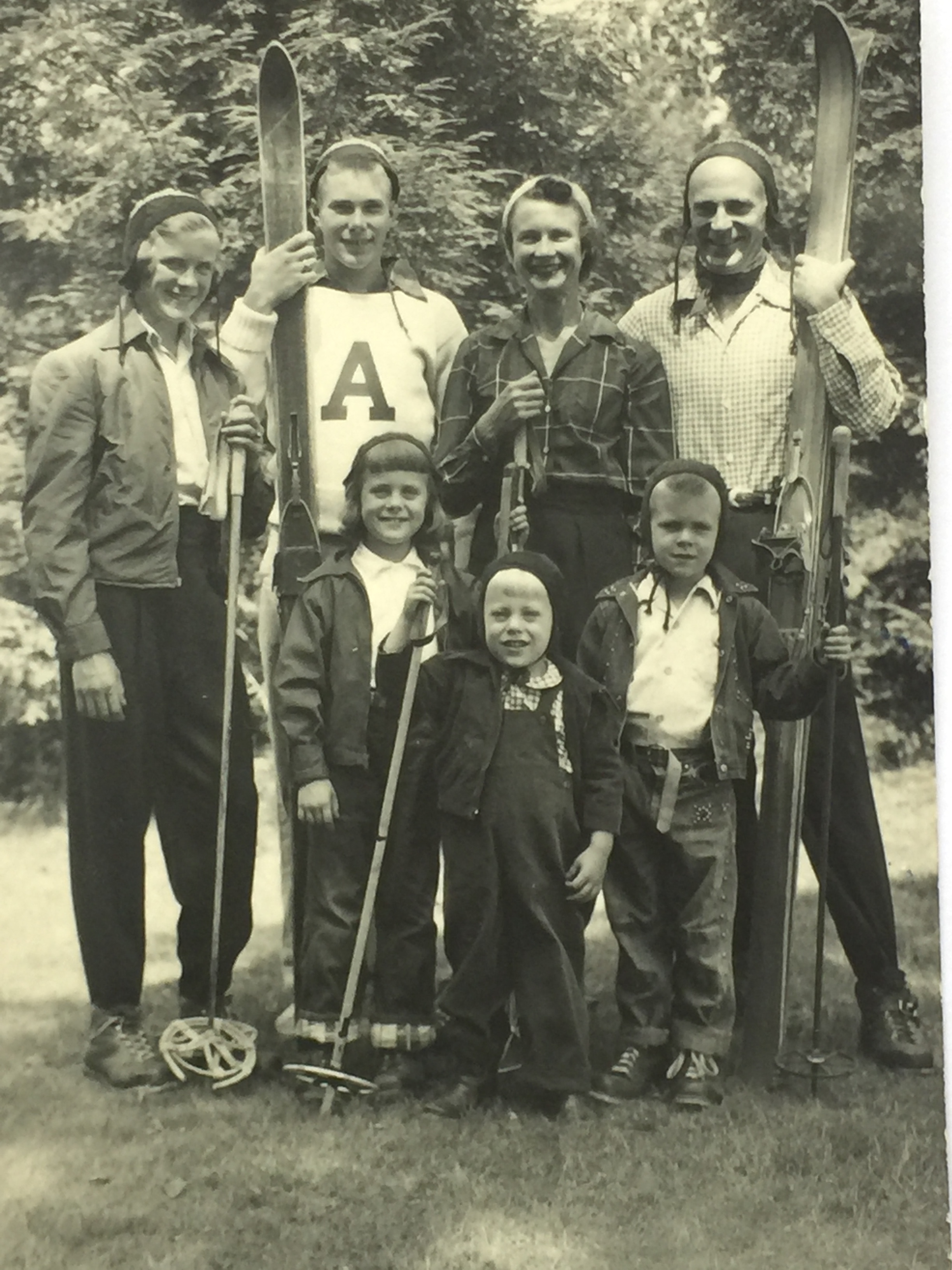

Re skiing, my parsimonious parents wouldn’t spend the $1.25 for a children’s lift pass, so I climbed the Lord’s Prayer on my hand-me-down Northlands, right past the signs that shouted “No Climbing!” which I wasn’t yet able to read. The wet snow stuck to the unprepared wood bases, so a sibling would have to meet me at the top to scrap off the encrusted snow layer. No one even suspected my eyes were so bad I was practically blind (nor would they until I was 9, which is also when I finally became worthy of a lift ticket).

When I got hungry, I’d go into the Wild Boar and look for a family I didn’t recognize and tell them my parents had left me behind. That was usually good for French fries and a cocoa, more than I could ever weasel out my parents, who were so observant of how I was outfitted that I once came out of my socks during a tumble. My skis took off downhill without me, the Dovre cable bindings still holding my leather boots, my thick wool socks sticking defiantly out the top.

Any hint of the skier I would become was as buried as a lost civilization, interred alongside my social skills. I didn’t emerge from my long incubation as a skier until I moved west in 1972. Social skills were gradually acquired thereafter.

I’ve been a western skier for so many years, my memories of New England might as well be from another lifetime. Yet no matter how far away the crown of a tree grows from its roots, it will forever be dependent on them. My roots are in southern Vermont, and there they will abide near the pasture where my parents’ ashes lie in wooden boxes.