A rock impresario who happens to be a dear friend of mine ascribes the secret of success to “timing and lighting.” That’s an apt aphorism for my office career at Salomon in the early 1980’s: I was in the right place at the right time, for nothing creates opportunity like chaos.

Just as I was settling into my new duties as Educational Services Administrator, the lowest possible clerical rung on the ladder to success, the ski market went into one of its periodic paroxysms. (Later on, as a product manager, it would be one of my myriad duties to calculate these market swings.) Overnight, sales plunged from a high-water mark of 500,000 sets of bindings, which Salomon rosily re-calculated as 1,000,000 pairs of toes and heels, because they were packaged separately.

When I rolled into the Peabody, MA offices of Salomon North America, binding sales were in free fall. We had other things to sell, like ski gloves that bled blue dye when they got wet, orange bags that were, well, extremely visible, binding covers sold in the Midwest as gaiters and a couple of goofy new boots that barely made in a dent in what was then a huge boot market. Injury lawyers were suing us anywhere from 400 to 600 times a year. Adding to the fun, interest rates were sky high and bankers were leery of our prospects.

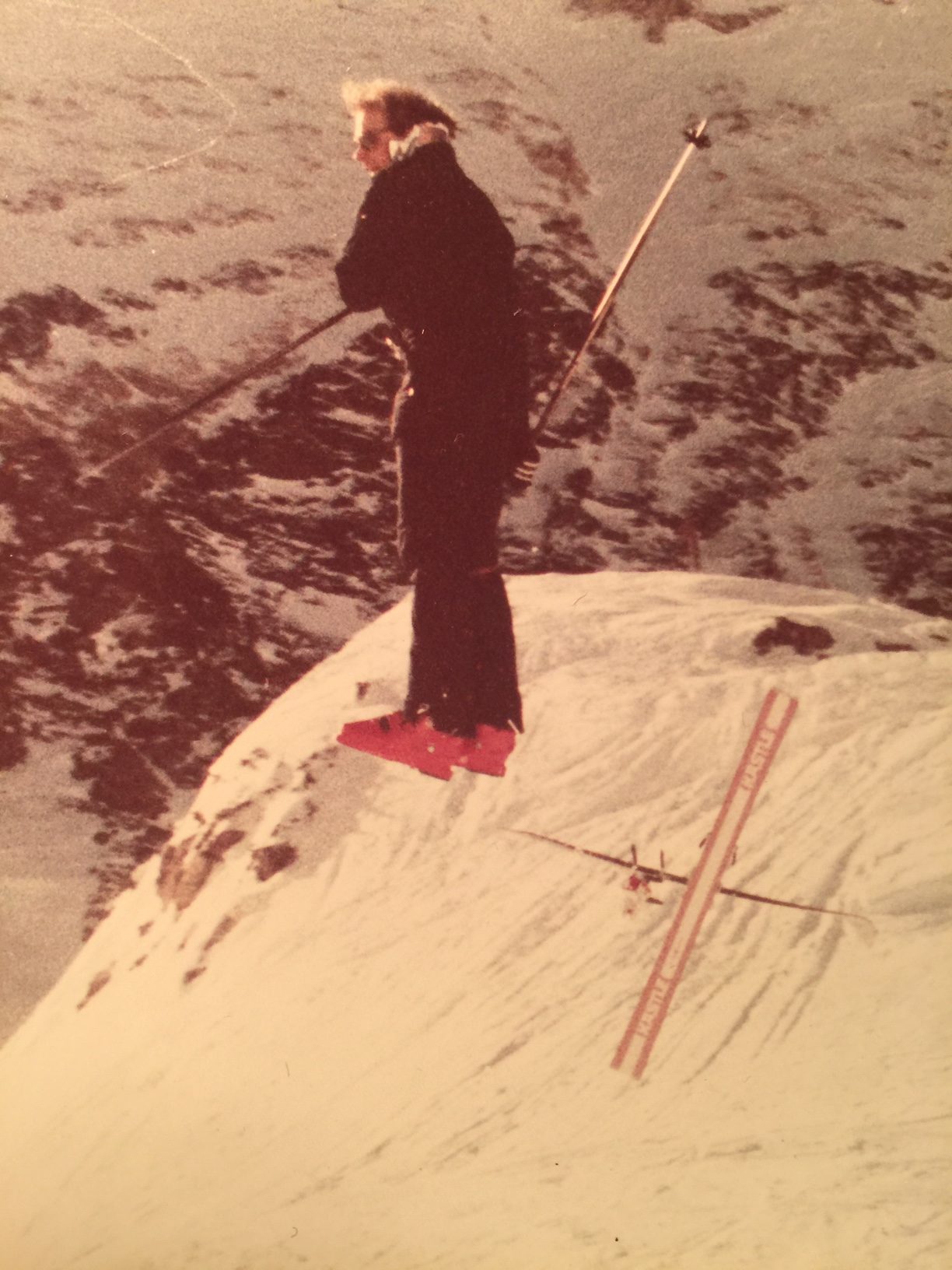

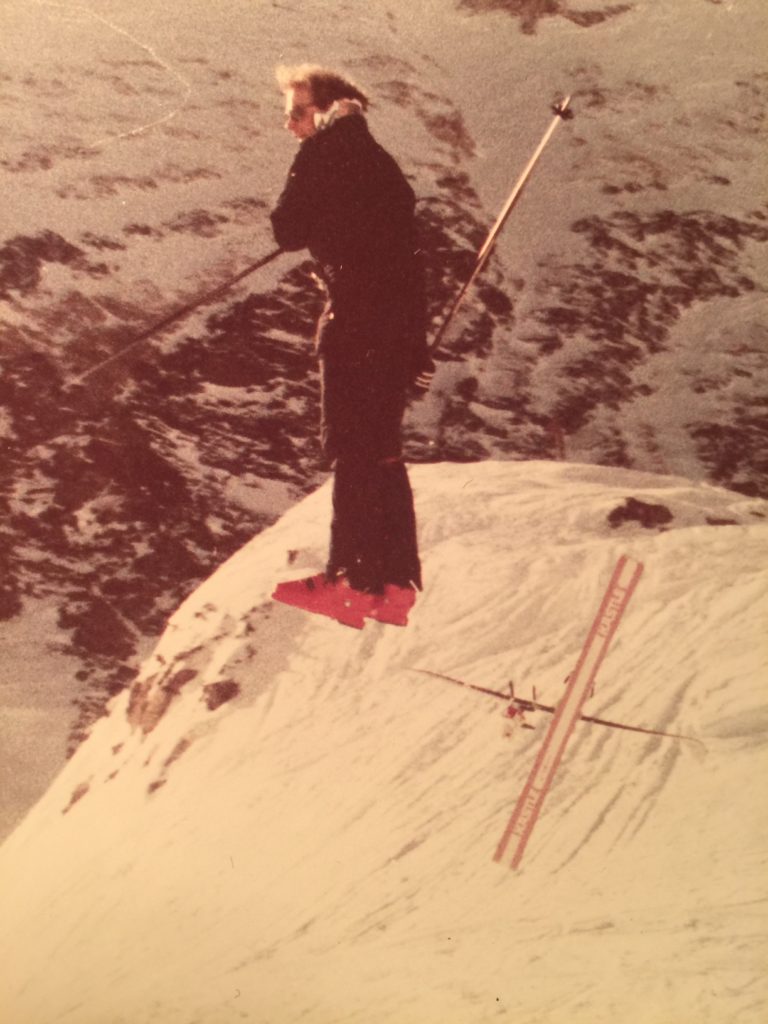

I demonstrated my confidence in the SX91 by attempting a heli on a pair of 213cm Kastle Super G skis. The SX91 became the boot that bought Taylor Made. I created a full body divot at the base of a sign that read, “Danger Cliffs.” Location: bottom of Mark Malu, Snowbird, UT, January, 1986.

While sales swooned, I kept my head down, cranking out media to support the binding and boot certification programs. Thanks to my transparent insignificance, I was spared when the corporate scimitar swept through the boardroom, putting the entire management team on the street. This precipitated a reshuffling of the remaining cast and by the time the dust settled, my mentor and corporate spirit guide, Joe Campisi, quit to launch a high-end demo/rental business in Park City.

This created a void where there used to be a Binding Product Manager, which sucked me into the position as I was the closest person next to it. This was the first of what would become a rapid agglomeration of titles and duties as circumstances conspired to chart my corporate course.

I don’t know what falls under the heading of “product manager” elsewhere, but at Salomon it meant serving two masters: the commercial zone you represented (North America, in my case), and the product division at the parent company. Anything and everything concerned with how that product was presented fell under the product manager’s purview, from the fine print on the in-box instructions to the liability release on the bottom of a rental form.

I’ll spare you the ten-page, single-spaced list of all the duties and thingies for which I was responsible, (aka, the budget), but just to give you a taste it included the binding technical manual, carousels of slides for a four-hour tech/promo mind grind called certification, along with three to six videos per year, cassettes of every presentation (so field personnel could hear it over and over), brochure copy, training bibles, representing Salomon on the SIA and ASTM ski safety committees – where I served as chairman and general secretary, respectively – comic videos like The Great White North to keep the reps awake and training sessions so long and intense they were rated by how many shirts I sweated through.

And that was just for bindings.

By the way, I could not have been more naïve. I would literally work all night in the Peabody office – the fair Stephanie would bring me dinner – while every bouncer in every strip joint along Route One greeted the Eastern U.S. Division chief by name. (I could say more, but this is a family publication.) Once our Albertan rep, Bob Krysak, called my line at the Reno office at 11:30 PM just to see if I would answer. I did.

Your esteemed Editor with Walter Duvall, the enigmatic tsar of the East who would baffle western dealers with his conversational excursions. His black eyes aren’t due to goth makeup but a lifestyle that didn’t involve sleep.

When the boot product manager (who would go on to found Realskiers.com) proved unreliable in the reporting-for-duty department, it was suggested that I assume his portfolio, as well, as I’d been doing it already. This went over so well that the same concept was later applied to the accessories business, cross-country boot/binding systems and a ski division that wasn’t going to make a ski until well after I was gone.

Remember that dual-loyalty business inherent to product management, with one foot planted in the mothership, the other in her satellites? On the R&D side, we were killing it, with one market-disrupting product introduction after another. The SX91 was the tipping point, the phenomenon that fueled the acquisition of Taylor Made and thereby forever altered the course of the Salomon brand. This same period saw Salomon enter the sleepy cross-country category and steal a 40 percent share for its SNS system overnight.

Given the products I had to work with, my achievements amounted to no more than the usual corporate striving. All I added to a standard formula was an insistence on the consistency of our message. Ergo, all the training time; hence all the cassette tapes. Whether you’re traversing Texas, Wyoming or New Jersey, you can listen to the script you’re expected to recite. As a trainer, I couldn’t change your social style, but with any luck I could keep the message from getting lost.

I apologize to all who still cling to my listing line of thought, but I feel obliged to point out that my core mission was to train a group of people who seem to have been preselected for their inability to be trained. And that was the ground on which my other foot stood.

My overriding ambition was to create, invigorate and reinforce a common message, so that whatever a Salomon rep said in Vermont wouldn’t deviate from the story told by a rep in Colorado. While this is a challenge all marketing organizations have to contend with, the task at Salomon was complicated by the fact that the North American field force was comprised mostly of non-conformists, troublemakers and iconoclasts. Getting them all to sing the same song would take a miracle.

As at that time miracles were outside my area of expertise, I chose the next best training tool, humor. If you want your rep force to read a product update on why white polyamide boot cuffs were turning yellow while still in the box, you headlined it “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” and delivered the news bundled in bon mots. If my messages weren’t memorable, they weren’t worth writing.

One of the secrets to Salomon’s success was whenever it created a new product, it created a story about the product at the same time. No innovations issued from R&D without first being swaddled in a protective layer of storytelling. I didn’t know how to make the baby, but I knew how to weave the blanket it was wrapped in.

My role, essentially, was to get both the baby and its blanky to the trade and consumer markets intact. Just to raise the bar a little higher, the French parent company decided, in its Salomonesque wisdom, to cut the U.S. market in two.

You probably didn’t realize the U.S. was once subdivided into semi-autonomous East and West regions.

In case the reasons why aren’t transparent to you, one rationale was both halves of the country had its own Salomon warehouse and made its own forecast, the foundational numbers upon which the business was based. True enough, but the schism between Salomon East and West also reflected the opposing worldviews of the men who ran them, Walter Duvall, who controlled his eastern minions with a drill sergeant’s iron grip, and Tom Corlett, who acted more like a life coach at The Esalen Institute. Their narratives of where the market was heading did not align.

My take is the French used the oil-and-water relationship between Duvall and Corlett as justification for subdividing the American market and thereby diluting its influence over the international direction of the brand. At its highest levels, Salomon management was comprised of an old guard who ran the various product divisions. At the time, we were fighting a huge influx of grey market boots that was doing serious damage. A lot of fingers were pointed and the boot division had to make a huge investment in product marking and tracking to placate the Americans. The kerfuffle didn’t make us any friends at court.

I remember the relief I felt when, at long last, I was allowed to hire two assistants to help shoulder my workload. I couldn’t wait to work with Michel Benoit and Kirk Langford, but it turned out I would wait a lifetime. No sooner did they accept their new positions than the French announced they were going to phase out the Reno distribution center and relocate all Zone personnel to the North Shore of Boston.

I wasn’t going back. I felt like I spent more energy wrestling with factions within my own company than combating our competition. I was leaving a very strong company with absurd market share in every segment it seriously addressed and I knew I’d never work for another team quite as strong as the one I was departing. But it was time.

A rational person probably would have stayed with the company, but I’ve always been more of an idealist. Never mind what is; tell me what can be. My dream was to write, never mind that a witty office memo isn’t an augury of novelistic success. I would subsequently write a fistful of highly rejectable screenplays and an exhausting demonstration of why I would never be a novelist.

Call it luck or call it fate, but I was barely out of the Salomon nest when John Fry, representing The New York Times Magazine Group, called to inquire if I were interested in becoming an equipment editor, and if so, did I have a sample of my writing I could provide?

And this is where we shall pick up the thread of our narrative when next we broach the subject of my journey from a child who couldn’t see where he was going – my eyes were a hot mess from birth – to a 37-year old man who still couldn’t make out where he was heading