The average American skier buys a new ski every 8 to 10 years. (Please don’t tell Donald Trump we alluded to any American as “average.”) For every gear junkie adding to his or her arsenal every other year there’s someone who, as far as the ski industry is concerned, goes dormant for over a decade.

Twenty years ago, when a sizeable slice of the current ski population last looked at new skis, my position as Equipment Editor for Snow Country Magazine and Snow Country Business gave me an insider’s view of how all major brands performed both on the snow and off the sales wall.

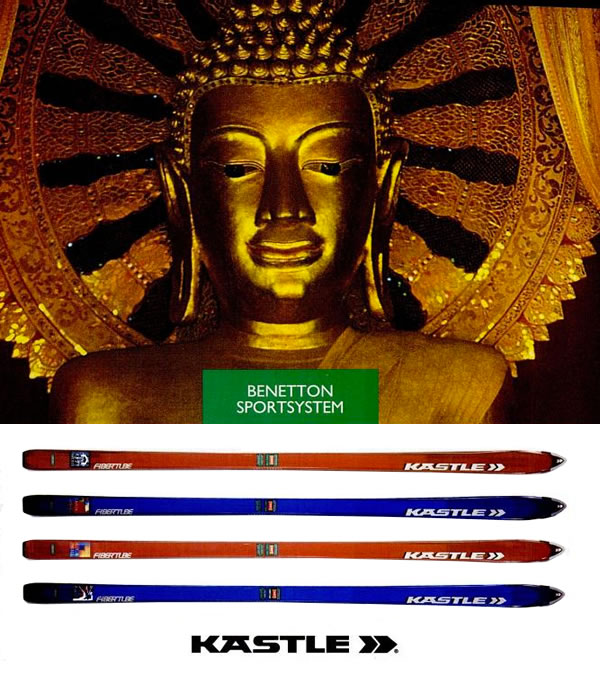

If you were taking bets in 1995 as to which brands would implode the soonest, Kästle and Blizzard would have been frontrunners. Kästle had just unveiled new models with names like Anti Thesis and Syn Thesis, as if Hegel or Marx (Karl, not Groucho, despite the comedic overtones) were leading the design team. Made with air channel cores – aka, “hollow” – the Thesis skis would have been the worst of their day except the next year Kästle made what looked like a giant tick-squasher called the B-52. “Hilarious” is the kindest epithet that comes to mind.

At least Kästle took a stand, even if it was on quicksand. Blizzard was so adrift they barely registered in the US, with weak distribution and zero market traction.

Yet today Blizzard and Kästle are not only still standing, they’re rocking. The brands they outlived include Authier, Dynamic, Volant, Lacroix, Olin, Pre, RD, S and Tyrolia. (Feel free to chime in with others; that’s what Facebook is for.) The erstwhile ditsy wallflowers are now among the most cultivated and coveted belles at the ski ball.

The peak-and-valley trajectory traversed by Blizzard and Kästle has been retraced by every major brand you can name. Rossignol is currently riding a hot streak that’s taken them to the top of the heap, but it wasn’t that long ago that a mercifully short-lived ownership by beach brand Quicksilver had the iconic French company in irons.

Head was once so dominant that a ski shop without the iconic brand wasn’t credible; all it took was association with a binding recall in the late 1980’s to trigger a downhill slide that reached its nadir when it was absorbed into the Austrian state-owned tobacco monopoly. (Yes, there was even a Head cigarette brand.) Head’s residence in the US doghouse was only temporarily interrupted by an upward wave that crested when shaped skis became an unstoppable force. Now Head is steadily re-ascending, fueled by phenomenal racing success and a sterling reputation for quality.

Salomon had home runs like the X-Scream and foul balls like the BBR. Elan earned kudos for the its pioneering SCX, but tripped up on the 45mm-wide Stiletto.

In a market addicted to frequent model renewal, the once-a-decade buyer might as well be in a coma while the world spins on without him, making skis shorter, fatter, shapelier and lighter while he or she takes a long time-out. During this Rip Van Winkle slumber, all major brands will have invested in new technology several times over, fortunes rising and falling in a roiling market until all that’s recognizable to the freshly awakened ski buyer is a smattering of brand names.

Outdated impressions of what’s hot are not useful foundations for present buying decisions. The ski market is fluid and fiercely competitive, compelling all brands to incessantly improve processes and products. Information that is several seasons old is about as helpful as a dustyEncyclopedia Britannica.

Brands that retain loyal fan bases through turbulent times don’t succeed by standing still. Völkl has maintained a strong following for the past 15 years despite thoroughly transforming the behavior of its core products, model by model, over that span. In other words, whatever it meant to “ski like a Völkl” in 2000 doesn’t apply fifteen years later.

Whenever a brand surges in market share, the engine behind the push is almost always fueled by product quality. According to data from a reputable source, the brands making the biggest upward move in the U.S. last year were Rossi, Blizzard and Head. While marketing and commercial practices play a role in their success, all three of these brands got on their current winning streaks due to how brilliantly their star products perform on snow.

The present day ski buyer has the perhaps dubious benefit of two other seismic phenomena that were just emerging 20 years ago and still in a relatively infantile stage 10 years ago: the Internet and the explosion in garage or “micro-brew” brands.

The Internet created dozens of new outlets for ski sales (as their brick-and-mortar brethren were dying off) and inspired almost as many oracles of advice. (Realskiers, BTW, was formed in 1999 from the bones of Inside Tracks.) Like any tool, how useful the Internet is for researchers and buyers depends on how it’s used.

“Garage brands” are often made in actual garages

The blossoming of micro-brands, originally created to cover niche necessities like ultra-wide powder skis or competition-quality twin-tips, has spread across the product spectrum, although pipe, park and pow continue to be their strong suits.

In case these small-volume makers fly below your radar, they now include (by our ultra-unscientific survey) an entire Dr. Seuss-like catalog of brandlets: 4Front, 5th Element, 7 Mile, 9th Ward, Big Wood, Black Crow, Boone, Bomber, Bro, Caravan, Coalition, Deviation, DPS, Faction, Fat-ypus, Folsom, Goode, High Society, Humanity Snow, Icelantic, J Ski, Liberty, Lib Tech, Lucid, Kitten Factory, Meier, Migrate, Moment, Movement, Northland, ON3P, Praxxis, Primal, RAMP, RMU, Sego, Shaggy’s, Skilogik, Slant, Sporten, Surface, Tahoe Lab, Vishnu, Wagner, White Dot and White-doctor.

Most of these brands—but by no means all—aim at some slice of the youth market. If you’re a resort skier who stays away from the terrain park, there isn’t a lot these mini manufacturers have to offer that you can’t find from a major player. Lacking the R&D budgets of the established brands, low-output manufacturers also usually lack the quality control or finishing processes that are the hallmarks of more sophisticated, well-capitalized production.

It’s the best of times if you desire nearly infinite choice; it’s the worst of times if you have no idea how to choose wisely. We modestly propose that you use the precision tools onrealskiers to whittle away at the forest of options, and seek the counsel of your local specialty ski shop to help steer you toward a ski you’ll probably be riding for the next ten years.