A Visit with the Master

This article is an excerpt from The Clendenin Method©: Four Words™ for Great Skiing, by Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame member John Clendenin. While the complete book examines the art of all mountain and mogul skiing in greater depth than we can on the site, here are, in abridged form, key concepts to help any level 6 or higher skier improve performance, along with simple exercises to help skiers develop necessary skills to tame the bumps. Principal among these is the skill to manage, as opposed to maximize, speed in bumps.

John Clendenin: Not that long ago, I had an opportunity to acquaint my hero—and one of the greatest skiers of all time—with our program. Here is what Stein Eriksen had to say about The Clendenin Method™—

“The most important thing is John Clendenin’s ability to teach people how to ski.

“I’ve known John for years. He is a dedicated ski enthusiast with who has given his life to skiing and has done much for the sport. John has a lot of experience behind him, intelligence that matches his skiing abilities, a true love of the sport and a loveable personality. His skiing accomplishments speak for themselves.

“Especially important, John can communicate with skiers. With his accommodating openness, he attracts people to him and helps them get over any hesitation or fear they may have. John has a way of explaining complex things in simple terms anyone can understand. He uses words that help people relate to concepts easier.

“Some people are uncomfortable in the ski environment. The environment can be intimidating and sometimes people require psychological adjustment to become comfortable. They are hesitant, uncertain that they belong. John helps skiers overcome hesitation and fear, both in his indoor studio and on the snow.

“I am impressed by John’s ability to talk people into taking indoor ski lessons in Aspen, one of the best known ski resorts in the country. He is the one who has pursued and developed the ski deck; a tool I’ve always thought to be good for any skier at any stage.

“John has taken time to perfect his methods. He reduces intimidation in skiers by helping them first learn the technical part of skiing in his studio. On the mountain, they are often surprised by what they can handle with calm confidence.

“John’s method is simple. He relates to people and sees beneath to how they are feeling. John has an ability to give easy-to-understand explanations in simple words that help ideas sink in automatically, so that they become part of the skier.

“John Clendenin has the product to help any skier of any skill level. I endorse John and recommend The Clendenin Method.”

The Skills Inventory

This article is an excerpt from The Clendenin Method©: Four Words™ for Great Skiing, by Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame member John Clendenin. While the complete book examines the art of all mountain and mogul skiing in greater depth than we can on the site, here are, in abridged form, key concepts to help any level 6 or higher skier improve performance, along with simple exercises to help skiers develop necessary skills to tame the bumps. Principal among these is the skill to manage, as opposed to maximize, speed in bumps.

“John has style for days. He is legendary not just for winning Freestyle competitions at the height of the sport, but for doing it with style and charisma. Of course, he has just gotten better with time.

“I skied with him in the movie Fistful of Moguls, among other times, and he was ripping. He is so smooth. He has mastered the art of effortless skiing. His technique through the moguls is buttery smooth and efficient.

“I have seen him tirelessly develop The Clendenin Method™ to help everyone else learn to ski effortlessly forever and he has it down pat. I’m stoked to see him taking it to the next level. Go John. You’re the man!” —Jonny Moseley

In all sports, joy is achieved through mastery of fundamentals. Solid fundamentals create efficient movements that evolve into instinctive movements. As the knowing and doing become one, the joy begins. The Clendenin Method is dedicated to this journey. – John Clendenin.

The Starting Point

There are no “right” or “wrong” answers; by taking an honest inventory you begin the process of mastering moguls and the all mountain experience.

Mogul Skills Inventory

- I can ski fast on blue runs (OK on black), but get thrown around as soon as I enter bumps.

- When in bumps, I can make two or three turns, but then gain too much speed.

- I’m not sure what to do with my poles in bumps.

- The way I ski bumps is a lot different than the way I ski on groomed runs.

- Sometimes I get caught in a traverse across the bumps and it feels like I’m riding a wild pony.

- I don’t know whether or not I stem my turns in bumps.

- I do know the difference between a stem and a parallel turn entry, but have trouble sometimes with parallel entry in the bumps.

- I feel OK in moderate bumps, but not when it gets steeper.

- I like to warm up with a fast run.

- Sometimes I have to hop to get over bumps.

- I try to use my edges to control speed.

- I use my pole plant to turn.

- I enjoy all mountain skiing, but like to play with the basics of technique on groomed terrain.

- I eat all kinds of bumps for breakfast!

- I love to watch good skiers ski.

Skills inventory explained

This article is an excerpt from The Clendenin Method©: Four Words™ for Great Skiing, by Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame member John Clendenin. While the complete book examines the art of all mountain and mogul skiing in greater depth than we can on the site, here are, in abridged form, key concepts to help any level 6 or higher skier improve performance, along with simple exercises to help skiers develop necessary skills to tame the bumps. Principal among these is the skill to manage, as opposed to maximize, speed in bumps.

“Good skiers use two edges; great skiers use four edges” – S. Kane

This overview will provide a solid basis on which to build toward total control in the bumps.

Here are the inventory statements with an interpretation of the meaning of each of the elements:

1. I can ski fast on blue runs (OK on black) but get thrown around in bumps.

Speed can mask problems with balance and technique. One can get away with technical lapses on fast blues—essentially exercises in two-dimensional skiing—that become obvious as soon as terrain becomes multi-dimensional. This is often a clue that one or more fundaments of technique needs work.

2. When in bumps, I can make two or three turns but then gain too much speed.

This most often indicates reliance on hard, aggressive edging to control speed. Hard edges actually accelerate us and reduce our ability to control speed through turn shape. In this series, we’re going to focus on learning to use soft edges that allow us to drift up the bump, using turn shape to control speed.

3. I’m not sure what to do with my poles in bumps.

Many skiers are accustomed to using a hard pole plant to initiate the turn. The pole plant cues transfer of weight to an already stemmed uphill ski, guaranteeing that turn entry will be a wedge entry and not a clean parallel entry. This is where problems start!

4. The way I ski bumps is a lot different than the way I ski on groomed runs.

Technical fundamentals for groomed snow skiing and for controlled mogul skiing are identical. This difference in “techniques” indicates need for work on basics, which most often means eliminating tendency to enter turns with a wedge, however slight. As you will also see in Harald’s columns, many skiing problems start with wedge entry into turns.

5. Sometimes I get caught in a traverse across the bumps and it feels like I’m on a wild pony.

There is a large difference between drifting on a soft edge and traversing on a hard edge, which essentially locks the skier into a track from which it is very difficult to release the edge and begin the new turn. Drifting allow us to release and engage edges to avoid traversing over the straight backs of “dinosaur” moguls.”

6. I don’t know whether or not I stem my turns in bumps.

If you experience any of the difficulties described in items 1 through 5, chances are you are stemming.

7. I know the difference between stem and parallel turn entry, but sometimes have trouble with parallel entry in the bumps.

That you know the difference between wedge entry and parallel entry is positive and, while having trouble performing a move you know to be correct can be frustrating, this awareness actually indicates you are on the verge of a breakthrough—you are in position to begin rapid improvement.

8. I feel OK in moderate bumps, but not when it gets steeper.

This is usually because the skier lacks bone-deep trust in his or her technique. Psychological considerations aside, bumps actually make skiing easier. Bigger, rounder and steeper equals even easier. With trust in the solid fundamentals of bump skiing, which are the solid fundamentals for all skiing, you’ll learn to love the steep ones, not least because fewer hackers hack ‘em up! This, too, is an indication that you are poised for improvement. As we go along we’ll discuss the secret source of speed control which comes from scraping speed as we re-center on the uphill edge of the uphill ski.

9. I like to warm up with a fast run.

This gets back to number 1. Speed masks all kinds of problems. Virtually all top skiers warm up with slow, deliberate, technically perfect turns; lot’s of them. In fact, many top athletes make it habit to warm up with slow precision turns, gradually increasing steepness of terrain while maintaining deliberate and, above all, constant speed. This is harder than it sounds, but, not only is this one of the best ways to identify aspects of technique that need work, it is the very process by which that improvement is made. Remember, even Johnny Moseley wasn’t born with fully developed mogul skiing skills!

10. Sometimes I have to hop to get over bumps.

This is some skiers’ primary turn entry in bumps. At Camp with the Champs, we call it the ‘air stem’. The hop is from one big-toe edge to the other big-toe edge, from one hard edge-set to another hard-edge set. Often, our air-stem clients have gotten good at it. Unfortunately, they usually plateau until they return to basics. As Scott Kane of Aspen, a great skier himself, once said,” Good skiers use two edges; great skiers use all four!”

11. I try to use my edges to control speed.

Using hard edges to control speed is without doubt the most common mistake in mogul skiing. Hard edges accelerate us abruptly into the next turn by cutting off the finish of the current turn. This makes speed control difficult. It’s amazing how effective speed control suddenly becomes when managed by “drifting” up the mogul on a soft edge before making the transition to the new turn.

12. I use my pole plant to turn.

This usually translates as, “I use my pole plant to shift weight to the big-toe edge of my (already) stemmed ski.” It underlines need to practice fundamentals of parallel entry on groomed terrain before attempting real progress in the bumps, progress that does not rely on the pole as a turning crutch.

13. I enjoy all-mountain skiing, but like to play with the basics of technique on groomed terrain.

This is a very positive sign, as progress in basics is most likely to occur on groomed terrain, in deliberate and controlled turns. This is a powerful self-coaching method. Using it indicates solid understanding of the process of technical improvement.

14. I eat all kinds of bumps for breakfast!

I remember watching a golf tournament on TV. The player had to make a short putt to win and the announcer said “no problem, he eats pressure for breakfast.” I liked the phrase so much I added the word ‘bumps’ and use it as a slogan for the ’Camp with the Champs’. In a nutshell, this kind of thinking indicates a positive mental attitude, which is half the battle.

15. I love to watch good skiers ski.

There is not one great skier who doesn’t. If you habitually watch good skiers, you are on the right path to improvement. It often dismays us during Camp With The Champs to see how often students ski down and then stare at their feet or chat with each other rather than watch their coaches. Studying video of winning runs is a key part of World Cup training for many national teams. Studying good skiers can likewise play a key role in developing and honing skills.

Let’s now begin to explore practical, actionable techniques for taming bumps.

Defining the Four Movements: Drift, Center, Touch, and Tip

Camp with the Champs uses the Four Words™ as a simple and descriptive way to create understanding of the movements of efficient all-mountain skiing. These four words describe fundamental movements that give focus to the technical development of skiers. Each of these words (movements) takes on new meaning and depth as students progress on to black level skiing.

Drift (drifting): The skill used to shape the path of momentum while skiing.

Drifting should not be confused with skidding, which connotes unintended slipping of the skis off the intended path of momentum. A proper drift is intended and balanced. At lower levels, the focus is through the bottom of the turn. As skills refine, we refocus on the start of the turn.

Carving is drifting with minimal lateral displacement, whereas, in all-mountain skiing, we often redirect skis with soft edges to create the intended turn shape. Drifting can be described as the center of the ski matching the path of momentum. Therefore, with a ‘soft’ edge, the ski will slide across and down the hill. In a basic sense, we are drifting all the time, using turns to redirect our path of momentum.

Center ( and re-center): The skill of finding optimum equilibrium and stability while skiing.

Skiing is balance in motion. We are constantly moving to stay in balance. Functional balance is realized when we learn to center both fore and aft and from foot to foot. To center more than 50% of our weight with respect to one ski creates the stance or balance ski.

Touch (to touch the pole): The skill of swinging the pole and contacting the snow while skiing.

The pole tip is swung out and down the hill in anticipation of our new turn. Initially, the touch cues release of engaged edges. When fully developed, the touching of the pole cues the lateral, rotational, and vertical movements that enable us to release edges effortlessly into the new turn. At the highest levels, the swing and touch time the flow down the mountain, from turn to seamless turn.

Tipping (to tip the skis on or off edge): The skill of changing the angle of ski contact with the snow.

Changing edge angle is done either to initiate a change of direction or to facilitate drifting. Each of the four edges in a pair of skis plays a critical role in every turn and they way in which they relate dominates the Most Important Moment in Skiing.

The rest of this series will examine these concepts in detail, including presenting exercises to develop these essential skills.

‘John-isms’

This article is an excerpt from The Clendenin Method©: Four Words™ for Great Skiing, by Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame member John Clendenin. While the complete book examines the art of all mountain and mogul skiing in greater depth than we can on the site, here are, in abridged form, key concepts to help any level 6 or higher skier improve performance, along with simple exercises to help skiers develop necessary skills to tame the bumps. Principal among these is the skill to manage, as opposed to maximize, speed in bumps.

“Science is a way of thinking much more than it is a body of knowledge.” – C. Sagan

To The Point

These are simple sayings I often use to make or support a point. We like them because they can clarify complex issues and render them understandable on a different level than that involved in specific exercises and drills, which we shall begin after examining some pervasive mogul myths, next.

The more time one spends with a “John-ism,” the deeper and richer the meaning becomes. In a sense, these sayings summarize the global experience involved in expert-level skiing.

Sensations

“The more sensitive one is to sensations in the feet that relate to the center of mass (balance), the more effortless and functional skiing becomes.”

“The most important sensation in a ski turn is felt at the initial instant the skis go off edge and become flat. Most people step, hop, or twist their feet quickly through this moment. It requires patience to sense the edge change that gives one the ability to control the top of the turn.”

Balance

“It’s more important to develop a sense of where you are in relationship to center than to try to be centered.”

“Good balance is the ability to react to imbalance.”

“Time spent on centering, balance, and basic technical concepts shorten the path to advanced skiing.”

Skis

“It’s easier to ride a horse in the direction it’s going. You have more control of a horse you are on than one you are not. This is equally true of the uphill ski when initiating a turn. It’s a lot easier when you’re on it! “

“Stemming is like trying to ride a pony you are not aboard. That’s why many skiers in bumps look like they’re riding runaway ponies.”

“The big toe edge of the downhill ski is our security edge. The little toe edge of the uphill ski is the edge of Champions.”

Drifting in harmony

“Drifting is what what an inner tube does in the river. Great skiers ski with the current of the mountain, not by banging down like a bowling ball.”

Debunking Mogul Myths

This article is an excerpt from The Clendenin Method©: Four Words™ for Great Skiing, by Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame member John Clendenin. While the complete book examines the art of all mountain and mogul skiing in greater depth than we can on the site, here are, in abridged form, key concepts to help any level 6 or higher skier improve performance, along with simple exercises to help skiers develop necessary skills to tame the bumps. Principal among these is the skill to manage, as opposed to maximize, speed in bumps.

“Time spent on centering, balance, stance and basic technical concepts shortens the path to advanced skiing.” – J. Clendenin

Let’s separate some fact from fiction. Only by becoming aware of inefficient elements in our technique can we begin the process of change.

Myth 1: Stance should be wide for stability.

Myth 2: Hands should be as far forward as possible, poles in a vertical position.

We look for hands held comfortably in front of the torso, as if holding a breakfast tray.

Myth 3: Legs should exert pressure on boot tongues to drive tips into turns.

Myth 5: Balance can best be maintained on the big toe edge of the downhill ski.

We encourage early centering on the up-hill ski; not relying on and hanging onto the big toe edge of the downhill ski.

Myth 6: Skis should be turned when un-weighted or even actually in the air.

As one observer put it:

Myth 7: The best way to control speed is to jam the big toe edge at the end of the turn, like a hockey stop.

Again, as articulated by Joubert in 1960 in How to Ski the New French Way (and he still says it best):“ The skis are held on their uphill edges… while the upper body plunges downhill. This causes the skier’s center of mass to pass across the skis, affecting a smooth and automatic edge change.”

Basic Concepts:

Here are some of our basic concepts, concepts we explore in the rest of this series; they are at the heart of efficient skiing, in bumps and out.

Patience

“The most important sensation in a ski turn is felt at the initial instant skis go off edge and become flat. Most people step, hop, or twist feet quickly through this moment. It requires patience to sense the edge change that gives one the ability to control the top of the turn.”

Balance

“It’s more important to develop a sense of where you are in relationship to center than to try to be centered.”

“Good balance is the ability to react to imbalance.”

“Time spent on centering, balance, and basic technical concepts shorten the path to advanced skiing.”

“The more sensitive one is to sensations in the feet that relate to the center of mass (balance), the more effortless and functional skiing becomes.”

The ski

“It’s easier to ride a horse in the direction it’s going. You have more control of a horse you are on than one you are not. This is equally true of the uphill ski when initiating a turn. It’s a lot easier to control when you’re on it!”

“The big toe edge of the downhill ski is the security edge, the ‘edge of fear.’ The little toe edge of the uphill ski is the edge of Champions.”

The mountain

The next installment begins to present exercises to improve mogul skiing performance—in fact, all skiing performance!

Drifting — moving across snow

This article is an excerpt from The Clendenin Method©: Four Words™ for Great Skiing, by Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame member John Clendenin. While the complete book examines the art of all mountain and mogul skiing in greater depth than we can on the site, here are, in abridged form, key concepts to help any level 6 or higher skier improve performance, along with simple exercises to help skiers develop necessary skills to tame the bumps. Principal among these is the skill to manage, as opposed to maximize, speed in bumps.

“The more sensitive one is to sensations in the feet that relate to the center of mass, the more effortless skiing becomes.” – J Clendenin

The “Double-edged Ski”

Shaped skis changed the way people ski. Whereas not too long ago most skiers were content to skid pencil skis about the hill, now many are concentrating on “carving” long, static, hard-edged arcs, no matter the terrain or conditions. There is nothing inherently wrong with hard-arc turns under appropriate conditions, but limiting one’s technical tool box to a single, aggressive carved turn makes little sense and is almost guaranteed to all but stop technical progress in moguls, deep snow or any other kind of “3-D” condition.

One technical skill that all great skiers share is the ability to regulate the edge by feathering it as needed for various tasks, including shedding excess speed in moguls. These skiers are able to manage the carve across a spectrum from hard-edge, hard snow rail-carving to long, lazy, mega-radius, soft-edge drifting. This skill is essential to efficient mogul skiing. In fact, this skill is essential to all high-level skiing. This is called drifting and it allows the skier either to maximize speed with minimal lateral displacement, as in a race course, or to manage speed with soft edges, as is desirable in moguls.

At the highest level, the Freestyle World Cup, it is instructive to note that reigning World Cup mogul champion Jeremy Bloom uses a little toe edge drift to manage his maximum possible speed. Fast though it may be, it is still managed speed.

Carving and Drifting vs. Skidding

Before the emails start flying in, let’s define two kinds of turn, skidding and carving.

Carving can range the gamut from hard arcs to lazy drifts and we consider a turn to be a carve when the entire ski displaces laterally on a controlled, balanced, intended path. Lateral drift can range from virtually none—hard-arc GS turn, for example—to substantial drift with feathered soft edge.

A skidded turn, on the other hand, is one in which the tail displaces laterally at a faster rate than does the tip and causes an unintended slipping of the skis away from the path of momentum. Here are what some tracks might look like:

clean carve

drift (soft edge)

skid

traverse

Mogul Skill #1 -Drift

Drifting is the first skill we focus on in our quest to tame the bumps. Here are some exercises we use to help develop a strong sense of edge-feather and controlled drifting.

Drifting begins with the ability to slip down the fall-line and feel uphill edges control momentum. The ability to distinguish between drifting and ‘traversing’, in which the edge scribes a hard-edged straight track across the hill with no downhill lateral displacement, is a basic tool for all-mountain skiing.

How to make this distinction is one of the most powerful “secrets” in all of skiing. It is also one of the easiest skills to develop.

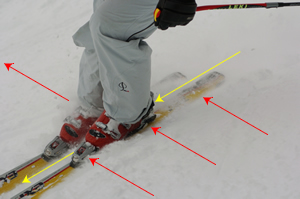

What this means is that the little toe pad is the only region of the foot through which one can manage pressure on the uphill edge of the uphill ski in order to monitor and control edge angle and rate of drift. Similarily, the ball of the foot (shown at left) is the only region of the foot through which we can sense and control pressure and angle of the uphill edge of the downhill ski. Note how much larger the little toe pad is.

There is, however, a catch. In order to develop awareness of the little toe pad, the skier must be moving with some sort of lateral downhill drift, which includes side slipping; it is nearly impossible to isolate feelings from this region when standing still and even more difficult when the skiers is traversing on the little toe edge—and completely impossible to detect when the skiers is standing on the big toe edge.

Here the skier side slips, alternating pressure from uphill to downhill ski and back and forth, developing awareness of the sensations delivered through the little toe pad, as in the image below. As conscious awareness of these sensations increase, so does the skier’s ability to manage the edge angle of the LTE, a key component in efficient drifting.

Here are some drills we use to help skiers develop the skill of drifting:

Drifting is balanced and intended. Skidding is sliding without control. With this sense of control, shape can be added to the slipping with fore and aft movement. Drifting on green level introduces speed control through turn shape.

Develop awareness of feelings in the feet that control the skis when drifting across the slope (on both edges in both directions).

Drift to specific locations (create fan-like progression on soft edges).

Expand ability to control the path of the drift (try different radius turns on similar terrain).

Learn to drift on both feet in each direction.

Learn to drift on each foot in each direction.

Find the flat spot* at turn initiation and focus on controlling the drift early, from the top of the turn.

Develop progressive edging skills (active feathering and increasing of edges) to direct the path of momentum, alternatively tightening and opening up the turn radius.

* If the phrase “flat spot” seems mysterious, have no fear; I’ll illuminate the concept fully in an upcoming installment.

Centering — the most important move in skiing

This article is an excerpt from The Clendenin Method©: Four Words™ for Great Skiing, by Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame member John Clendenin. While the complete book examines the art of all mountain and mogul skiing in greater depth than we can on the site, here are, in abridged form, key concepts to help any level 6 or higher skier improve performance, along with simple exercises to help skiers develop necessary skills to tame the bumps. Principal among these is the skill to manage, as opposed to maximize, speed in bumps.

“It’s more important to develop a sense of where you are in relationship to center than to try to be centered.” – J. Clendenin

Four-edge skiing—from the Center

“Balance” may be the least precisely defined word in ski instruction.

Certainly the skier above is in near-perfect balance, but something else is going on, something arguably more important than merely being “in balance.”

Here it is in stop-action:

Now, please consider these skiers—

Both are balanced, but, and this is the critical point, only the skier on the left is both balanced and centered. (Yellow circle denotes center of skier’s mass)

The skier on the right is in the classic and all too common stem entry position, a stable position, but not centered. His skis essentially form a triangular base, which makes him as stable as a pyramid. Stable though it may be, the wedge-entry is essentially a defensive position and a position from which it is almost impossible to manage momentum along a planned path.

The skier on the left is both balanced and centered. This is an important distinction. Because her center of mass is balanced precisely over her outside/soon-to-be-downhill ski as she approaches the fall line, Eva can easily and subtly move her center over either ski and is centered fore/aft as well.

Put differently, she can lift either ski at any time, something our stemmer cannot do without falling.

Which brings us to “the most important move in skiing.”

Mogul Skill #2- Center

The second of our four words, “center“, describes the orientation of the skier’s center of mass relative to one ski or the other and fore/aft on that ski. A skier who is centered is always in balance, while not all skiers in balance are centered.

Watch Eva’s skis closely:

Let’s examine this in more detail.

In the first image from the above animation, Eva is centered with respect to the outside, soon-to-become-downhill ski.

As she enters the final phase of this turn, she progressively re-centers to the inside-soon-to-be-uphill ski.

Here’s how she does it:

In figure A, as she crosses the fall line, Eva is beginning to weight the little toe edge of the uphill/inside ski progressively, as she draws the ski beneath her center of mass. In figure B, re-centering is complete; the little toe edge of the uphill ski has become the weight bearing edge. Eva drifts, feathering this edge to control speed; note how much more snow-spray is now coming from the little toe edge of the uphill ski rather than from the big toe edge of the downhill ski. Eva is poised to touch and tip into the next turn, balanced, centered with speed under control.

This is one of the most subtle moves in all-mountain skiing and the moment when the success of the next turn is assured. It is the key balancing move in mogul skiing and prepares the way for the most important moment.

The principal technical problem : a brief case study

Convergence, whether of knees, boot tops or ski tips, always points to a problem. This photo caught her shifting her center of mass from her downhill ski to her uphill ski just before the turn. To accomplish this weight shift, she had to slide her downhill foot away from her center in order to engage the big toe edge. This is known as an abstem. The edge engagement of the downhill ski, along with her firm pole plant, gives her the resistance needed to push off and shift her weight.

Separating feet to shift weight creates convergence. In this case, had she re-centered on the uphill edge of her uphill ski earlier in the turn, her skis and boot tops would match and her feet would remain beneath her center. In addition to eliminating convergence, early re-centering on her uphill ski would also have eliminated the need to push off (ab-stem) the downhill ski.

Exercises

Here are several exercises that help develop the all-important skill of early re-centering. The purpose of these exercises is to create awareness of subtle moves in the feet that relate to the center.

1. Moving Center to re-balance:

The skier stands across a groomed blue level slope, with feet separated approximately ten inches. Focus and awareness are on the uphill edges of both skis. The skier senses where he or she feels pressure on each foot, whether it is on the big toe pad or on the little toe pad (as explained in detail in a previous section).

The skier re-centers on the uphill ski while keeping feet separated and steady. The skier will sense where pressure is felt on the uphill foot. As the skier steps back and forth from foot to foot, it is easy to notice how much the center (navel) moves. We repeat this in both directions.

2. Sliding the ski beneath Center:

fig. 1 – centered on downhill ski

fig.2 – centered on both skis

fig. 3 – centered on uphill ski

3. Practice Hockey Stops/Side-Slipping

The skier makes several ‘hockey stop’ turns in each direction, ending centered on the uphill ski. How the skier does this is critical. Using a strong edge, especially on the big toe edge of the downhill ski, as most people do, will cause the ski to chatter. The goal is to do the exercise without causing skis to chatter by initiating the ‘hockey stop’ on a soft edge and progressively adding edge angle to the uphill edge of the uphill ski as it moves beneath center and becomes the weight-bearing balanced and centered ski.

fig. 1

fig. 2

fig.3

fig. 4

This move—along with #5 below—hones ability to control speed in the bumps. Where some skiers go wrong is in attempting to “get on” the uphill ski rather than allowing the uphill ski to slide beneath center, a vital difference shown in exercises #1 and #2. In other words, they move to the ski. The move that needs to be incorporated into the turn mechanic is to allow the uphill to ski slide beneath center. This is the most important move in skiing.

4. Ski down the fall line on a groomed, green-level slope, with skis separated about the width of 2 fists—8″

While moving straight down at a moderate speed, the skier touchs the pole and softly tips the inside ski. This tipping will initiate an effortless turn. As the skis begin to cross the fall line (fig. 2), the skier continues scraping the tipping ski (as it becomes the uphill ski) towards the downhill ski ( fig 3). This scrapping move should have the pressure of a squeege cleaning a windshild. This technical sequence automatically creates passive turn initiation as the tipping ski progressively becomes the uphill, weight-bearing, balanced and centered ski (fig. 4). This drill cannot be overdone; skiers should practice the exercise over and over, in each direction until the move becomes natural. Continue the exercise on a higher level by linking turns on groomed, blue-level terrain.

5. Link medium radius turns

This is to develop awareness of where pressure sensations develop on the foot while making the transition from one little toe edge to the new little toe edge, in other words from uphill ski to uphill ski. The skier should feel pressure on the foot migrate from one little toe pad to the other little toe pad as the skis cross the fall line. Again, it is crucial to manage the change in pressure from the downhill ski to the uphill ski beginning just as the skis cross the fall line.

The next installment introduces the often underestimated power of the pole touch, which will lead to the Most Important Moment in skiing.

The Light Touch — timing is everything

This article is an excerpt from The Clendenin Method©: Four Words™ for Great Skiing, by Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame member John Clendenin. While the complete book examines the art of all mountain and mogul skiing in greater depth than we can on the site, here are, in abridged form, key concepts to help any level 6 or higher skier improve performance, along with simple exercises to help skiers develop necessary skills to tame the bumps. Principal among these is the skill to manage, as opposed to maximize, speed in bumps.

“The big toe edge is the Edge of Security; the little toe edge is the Edge of Champions.” – J. Clendenin

It’s time to consider the relationship between the Four Words™: Drift, Center, Touch—this installment—and Tip (next and last).

While The Clendenin Method camp experience has shown that comprehension of the Four Words™ increases when the Words are presented as individual concepts, that same experience reveals the necessity for skiers to understand that each of the movements described by The Four Words™ interact and affect each other. All four major movements take place in a seemless flow and each affects the other three.

Moreover, and this is one major point of this article, the Touch not only triggers the Tip, but also profoundly affects centering, including fore-aft balance. The Touch triggers movement of the center of mass along the intended path, down into the “gravity well” of the new turn. This, along with avalament (the ability to absorb terrain features like moguls through extension and retraction of the legs), creates the flow of the skier down the mountain, in the same manner as an inner tube will float along with the current of a river.

Following the last Four Words™ installment, titled Tip, our final article in this series will examine the nature of the Flow and the way in which pole timing either compliments or inhibits efficient movement of the center of mass, which is at the heart of centered balance.

Major elements of the Touch.

Case Study : Plant vs. Touch

We’re going to focus on the pole swing and plant in this segment, but it is useful to note how the elements of the turn interact with each other and how inefficiency in one movement breeds inefficiency in all the other movements.

Consider the frames below the animation.

In fig. 1, our skier swings her pole too far forward, using large arm movements as she reaches to find a spot to plant the pole. Note that the pole tip is actually in front of her ski tips.

She also abstems (shoves downhill) her downhill ski and stands on the big toe edge of the downhill ski, rather than re-centering on her uphill ski.

Here our skier firmly plants the pole, using it as a crutch to brace against as she transfers her weight from the big toe edge of the downhill ski to the big toe edge of the uphill ski, remaining out of center. Perhaps even worse, her exaggerated reach has caused her torso to twist away from the path of momentum. This is entirely different from using the pole touch to cue tipping of the downhill ski into the new turn and is an all too typical movement pattern that renders efficient mogul skiing all but impossible.

In Figure 3, to the right, she is shifting here weight from one big toe edge to the other big toe edge and we see convergence of lower legs, boots and ski tops.

Our skier is trapped at this moment. She must lift (hop) the inside/downhill ski in order to shove it around in roughly the same direction that the now-engaged big toe edge of the outside ski is beginning to move in skidded fashion. Legs, boots and ski tops continue to converge, indicating that weight is being shifted from the big toe edge of the downhill ski to the big toe edge of the uphill ski.

She remains balanced on the big toe edge of the outside/soon-to-be-downhill ski. Notice how ski tips converge in a wedge. She may be balancing on the outside ski for the moment, but she is not centered. This creates problems as she prepares for the next turn.

Our hapless skier—who since these pictures were shot has made the paradigm shift, as we’ll see in the final installment—is likely doomed to fall further and further behind the flow with each new turn, until she is forced to bail out in a bumpy traverse across the mogul field in the “wild pony ride” that often overtakes big-toe-edge-oriented skiers in bumps.

Mogul Skill # 3 – Touch

As importantly, the Touch commits the center of mass to the path of momentum for the new intended turn. This commitment enables the skier to effortlessly release edges to begin the turn.

First, let us describe what we call “home position” of hands and arms. Note how Jason holds hands comfortably in front of torso, hips, shoulders and hands all in the same plane. Nothing about this position is exaggerated, nothing is tiring, nothing forces the skier out of center with respect to the path of momentum.

In fig. 1, note the position of Eva’s hands, arms and pole tips. Even though she is no lojnger in home position, she has hands even, arms level, slightly above the waist and fairly close to the body. She is not reaching forward with arms in an exaggerated, tiring position. Note how pole tips are out from and behind the body and not dragging on the snow.

Here Eva swings the pole forward with her wrist; the arm remains relatively in home base position; there is no large arm movement. Most importantly, this “flick” allows her to keep her torso quiet and her center connected with her path of momentum. She does not reach forward to place her pole beyond the ski tips. She has re-cntered with respect to her uphill ski, in preparation for edge release.

This is the moment of Touch. Eva is centered and balanced on her uphill ski pad of balance. Note how she touches the snow lightly, rather than planting the pole for balance or to use as a “weight-shift” crutch. The pole lightly taps the snow and, as in figure 4, cues release of edges into the new turn while simultaneously committing her center of mass into the new turn path.

Eva’s center has begun to move across her skis along the path of momentum of the new turn.

Eva has released the pole, is re-centered on her outside, soon-to-be-downhill ski and is well into the new turn after an effortless edge release. Her hands, arms and poles are returning to home position.

This diagram represents the proper location of the touch. Imagine a square drawn next to the front part of the ski, a square whose sides are equal in length to the distance from the toe of the boot to the front of the ski. The pole should touch at the point where lines drawn diagonally across the box from corner to corner cross. The skier will be able to make a touch in this location by flicking the wrist while forearm and torso remain in home position and without being forced to reach and stretch, an action which often takes the skier out of center, disrupting the path of the center of mass.

Here are several exercises to help you develop an effective arm swing and pole touch.

1. Practice skiing with hands and arms in effective home position.

3. Practice the touch as an integral part of the turn, cuing release of edges and movement of center into new turn path and not as a separate element that precedes the turn.

3. Practice flicking wrist to make the plant with little or no movement of forearm and shoulder.

4. Practice maintaining symmetry of both hands: width, height and level with respect to the horizons formed by shoulders and waist.

>5. Discover that the most natural stance and functional position of the hands is that in which the torso is connected to and moving along the path of momentum.

6. Develop arm swing prior to the Touch that matches the duration of the Drift.

a. cross the hill with skis about 2 fist-widths apart, centered on uphill ski.

b. touch pole, which will cue tipping of downhill ski and center of mass into turn

c. as the skis come to the fall line, progressively draw the old downhill ski (new inside ski) in toward stance ski, beneath your center

d. progressively recenter on the inside, new uphill ski

e. practice in both directions and in linked series of turns.

The Light Touch — timing is everything

This article is an excerpt from The Clendenin Method©: Four Words™ for Great Skiing, by Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame member John Clendenin. While the complete book examines the art of all mountain and mogul skiing in greater depth than we can on the site, here are, in abridged form, key concepts to help any level 6 or higher skier improve performance, along with simple exercises to help skiers develop necessary skills to tame the bumps. Principal among these is the skill to manage, as opposed to maximize, speed in bumps.

“The most important sensation in a ski turn is felt at the initial instant the skis go off edge and become flat. Most people step, hop, or twist their feet quickly through this moment. It requires patience to sense the edge change that gives one the ability to control the top of the turn.” – J. Clendenin

Patience Pays—Impatience does not.

It is also, in one sense, a moment of completion; the skier has finished the Drift, is Centered on the pad of balance of the uphill ski and has flicked the wrist forward at the end of the arm/pole swing to Touch. The light pole touch cues a Tipping of the downhill ski. This tipping creates a passive release of the uphill edge of the uphill ski, moving the center of mass into the path of momentum. This moment of passive release created by flattening the downhill ski is what we call The Most Important Moment in Skiing. It is the most important moment because passive release renders sensing the top of the turn effortless, allows the skier to use both legs as a piston to maintain contact with the snow and guarantees parallel entry into the turn.

In short, mastery of passive release of edges in the Most Important Moment allows the skier to master 3-dimensional terrain and, it almost goes without saying, groomed terrain as well.

Case Study : The Big Toe Trap

“Getting down” is not the same as dancing with gravity in joyful, seamless flow.

Mogul Skill #4 – Tip

Initial focus is on releasing edges. The release of engaged edges initiates a turn of the skis from across the fall line to down the fall line. As skills develop, the focus is directed to engaging edges. Engagement occurs when we maintain the tipping edge angle after the fall line and the skilled skier has the ability to progressively manage the edge angle for the intended drift.

Here are some exercises to develop patience and timing for the passive release, The Most Important Moment in Skiing

The Exercises

1. While making wide turns on a groomed green level slope, the skier drifts back and forth balanced on the little toe edge of the uphill ski. The skier focuses on where he or she senses centered pressure. The skier should sense pressure from the pad of the little toes to the beginning of the arch.

2. The skier drifts in one direction centered on the uphill ski. While drifting, the uphill edge is softly engaged when level against the slope (not over-edged into the slope). This soft sliding engagement while drifting requires a relaxed natural stance. While drifting and maintaining steady balance on the uphill edge of the uphill ski, actively tip the light downhill ski toward its little toe edge, as pictured above with spilling glass, making the ski flat to the slope.

3. During this drill, the skier does not actively tip or steer the weighted uphill ski. He or she allows the initial movement of the uphill ski (from edge to flat) to happen passively. Technically, the balanced, weight-bearing uphill ski remains passive as the active un-weighted downhill ski initiates the turn.

Tip and Tuck: one exercise for all four moves

We first introduced this exercise in connection with re-centering, but the whole truth is that it develops proficiency in each move and, as important, in the relationship between each of the moves. (for an action view of the exercise, see the animation above)

Practice this exercise on extremely gentle terrain, with emphasis on pole swing/touch timing:

a. cross the hill with skis about 2 fist-widths apart, centered on the uphill ski

b. touch pole, which will cue tipping of downhill ski and center of mass into turn

c. as the skis come to the fall line, progressively draw the old downhill ski (new inside ski) in toward stance ski, beneath your center, thus re-centering progressively on the inside, new uphill ski

e. practice in both directions and in linked series of turns — We call this ‘Tip-andTuck’.

This is a superb exercise to practice on otherwise boring roads, cat tracks and run outs and making the first run of the day at extremely slow speed while practicing this exercise is one of the best ways imaginable to begin a great day of skiing.

The more proficient a skier becomes at Tip and Tuck, the better he or she becomes as a skier, not only in 3-dimensional terrain, or at recreational speeds, but at all levels of skill, intensity and speed.