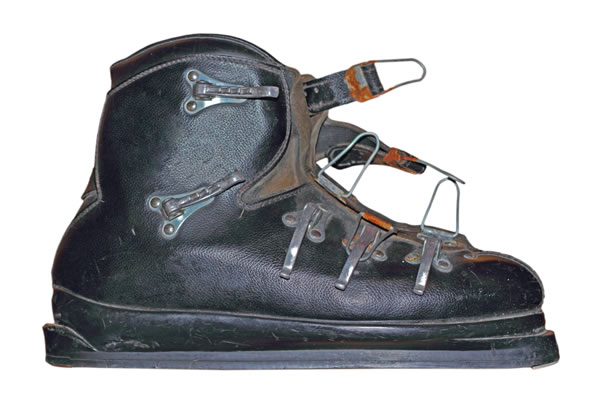

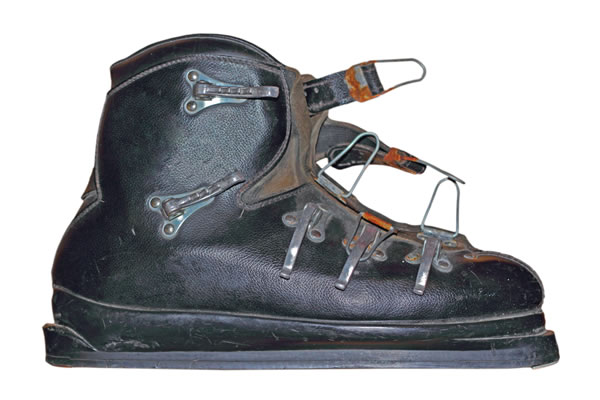

Alpine boots have most definitely changed since this model’s era…

but how much have they evolved lately?

One Saturday last season a customer of my generation was perched on the boot bench at Bobo’s enduring a somewhat frustrating fitting session – his first in many years – when he opined aloud that it didn’t seem like boots had changed much since last he’d shopped for them. I followed his gaze to our imposing wall of boots and had to admit he had a point: in many fundamental ways, alpine boots don’t seem to have altered their basic structures in the last 25 years.

Yet only the day before, in my guise as Editor of realskiers, I had huddled with Tecnica’s US product manger, Bart Tuttle, and the local rep, Dana Greenwood, to review the first samples of next year’s line. For the second time in as many seasons, Tecnica invested in improving their top-end technical boots, making new molds for the Mach 1 series to improve both fit and performance.

The size of investment to create a new set of molds is breathtaking and it’s even more daunting in a market that isn’t growing. So why would Tecnica – normally a cautious company – invest to such a degree in incremental change? Is the alpine boot market diddling with details when what the everyday skier wants is alternative archetypes to the status quo?

To begin to answer this question, let’s look at a couple of current boots that definitely deliver an alternative vision of the alpine boot, the Apexand the Dodge. These avatars of the avant-garde could not be more different in direction and execution.

The Apex keeps its unerring focus on comfort; the Dodge is intent on amping up performance. The Apex swathes the foot in layer upon layer of buffering; the Dodge brings the shell so close to the foot it feels like its melding into one’s skin.

Both the Dodge and the Apex demonstrate the historical difficulties all boot designers have faced: build a boot of pillowy comfort and performance is perforce compromised; reverse the equation and engineering lightening response entails a high tolerance for a confining fit. The current state of the art, however stagnant it may appear, represents the best compromise yet achieved in balancing these extremes.

To put today’s market in perspective, let’s look back at skiing’s infancy. Ski boots were any boots used for skiing. They allowed for movement in all sorts of directions that ankles aren’t designed to go, so cobblers found ways to reinforce the leather construction as it climbed gradually up the leg, encasing this critical joint.

As every skier knows, leather boots suffered the same fate as leather helmets. Injection molding in hard plastics produced a more consistent product at lower cost. But the plastic foot-containers didn’t much resemble feet on the inside, leaving it to the liner to provide comfort and adequate containment. Making the human foot happy inside a hard plastic shell that runs half way up the shin has been the focus of boot design ever since.

Iconoclasts like Dodge’s Dave Dodge and Apex’s Denny Hanson deserve recognition for challenging a lot of assumptions about what an alpine boot must be. But while the mavericks toil at the tip of the arrow, a lot of other clever people with fancy degrees labor in anonymity to refine the product lines of the major brands.

It was only a year ago that K2, the dominant ski brand in the US market, launched a new alpine boot division. They had the resources and opportunity to create any kind of boot they could conceive. Their engineers had a clear understanding of the existing market in all aspects, from materials to design to commercial landscape.

And what did this amalgam of wicked-smart people create from a blank sheet? A fairly traditional, two-piece overlap shell with a unique means of attaching the back of the cuff to the lower shell. It’s a very well executed product with a focus on free-skiing (as opposed to racing) attributes, but it’s not a radical departure from its contemporaries.

This observation isn’t meant as a veiled slight on K2’s efforts, but to underscore that the modern alpine boot has indeed moved forward since its inception. The best ideas are the ones that have survived the last fifty years of experimentation. Remember knee-high boots, air-bladder boots, wax liners, the Nava and countless iterations of single-buckle rear-entry models?

Given the high cost of industrializing a boot line and a flat world market, the chances of seeing a sea change in modern alpine boot design in the near term are slim. If the world’s population of skiers were to vote on a boot from the past they’d most like to still be using, it would probably be what was once the most popular boot on the planet, the Salomon rear-entry.

If history does indeed repeat itself, perhaps we’ll soon see some variation on the easy-entry theme rise to rule again. After all, with the widespread reappearance of the 1980’s walk-switch as a “hike mode” on today’s boots, can rear-entry be far behind?