How Fat Got Where It’s At & Where It’s Going Next

or, Why Fat Skis Need Fat Knees

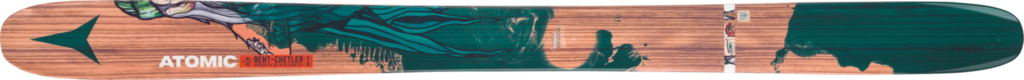

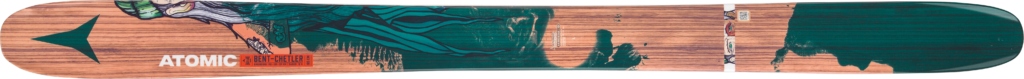

Atomic Backland Bent Chetler – 120mm underfoot

The Atomic Magic Powder first touched snow in 1990, a then ludicrously short (180cm) ski that was fat throughout, roughly as wide as two conventional skis of the day. It would be a few more seasons before the likes of the Völkl Snow Ranger, K2 Big Kahuna and Volant Chubb would materialize, helping create the powder ski category. Mainstream ski design was about to get caught up in the shaped-ski phenomenon, relegating the evolution of fat skis to the back burner. (Remember the ‘90’s ubiquitous all-mountain stick, the Salomon X-Scream? It was a miniscule 68mm underfoot.) But the seeds of change had been planted, and ever-fatter skis began to infiltrate major ski brands’ lines. Over the last decade what has been considered outrageously fat in one season looks skinny by the end of the following year. Ten years ago a ski 100mm underfoot was used almost exclusively by AK guides who had to race their own slough to a cliff band. Now 100mm-waisted skis are everyday rides for just about anyone who can say, “side-country.” How did this happen?

No question the fat ski craze has been fueled in part by dozens of ski flicks that have made the exotic seem familiar, showcasing what is possible on fat boards. But the accessibility of very fat skis for everyday Joes and Josephines has more to do with adaptations in ski design than it does with GoPro courage. As skis grow fatter they have to grow shorter or else they end up with the surface area of the Queen Mary. To make a short, fat ski both stable in straight running and carve-capable on groomed terrain requires the manufacturer to re-think dampening and get creative in the use of materials. Cores made with lighter wood are a start, but to really make any ski sing takes metal, which in large doses is not only brutally heavy but can be beastly to bend. So manufacturers have figured out how to use aluminum more sparingly (they call it “titanium,” but there is about as much titanium in most alu alloys as there is in a marshmallow), making thinner sheets, or perforating it, or using it in cutout silhouettes narrower than the ski. The result is an ever-wider array of ever-wider skis, pushing the “average” ski waist width to around 98mm, with tips and tails wider still.

When ski designers first tripped over the 100mm threshold, they weren’t thinking about how their new kids would perform on hard pack. That notion was discarded some time before noon on day one of the planning phase. A couple of years later, when still fatter skis became commonplace, 100’s didn’t look so chubby anymore and everyone forgot how specialized this shape was supposed to be. This made it easy, at least conceptually, to blend 95’s and 98’s and 108’s all in the same behavioral bundle, in the process throwing a blanket over a vital dividing line, obscuring it from public view.

There are skis made today around 108mm underfoot that are not inherently much different than a carving ski, albeit one with an eating disorder. Yet that 108mm ski looks much different to your knee than the slimmer siblings from which it sprang. Soft, fluffy snow with little resistance masks this difference, but once the surface is hard and efficient at translating energy, and the skier sets about tipping the fat board as if it were a slalom ski, every errant weight shift imperils one ligament or another.

Without a proper injury study, we can’t say exactly how wide a ski is too wide for any given skier, but suffice it to say that you shouldn’t arbitrarily grab your favorite fatty on a day you’ll be cruising groomers. If you’re using a smear-stick that barely exposes any edge to the snow no matter how you tilt it, your knees may be safe but I’d take out collision insurance for everyone else on the hill. The best directional fatties will hold a carved turn just fine, but you better know the secret to making a smooth move to the edge.

An obvious inference of this argument is that people with narrower knees—commonly referred to as women—have an even lower tolerance for super-wide skis. Any ski over 100mm underfoot is effectively a Powder ski for a female. Any additional surface area underfoot is a bonus on a deep snow day but a liability in almost any other condition.

Reverting to a unisex worldview, an interesting phenomenon is occurring in the Big Mountain arena, skis from 101mm—113 mm at the waist. As happened with the 98mm club over the last few years, manufacturers are offering more models with the potential to perform brilliantly anywhere on the mountain; but where many skis are undeniably capable, it doesn’t automatically follow that the skier has the mechanical wherewithal to safely direct this capability. The question is no longer, “Can a Helldorado hold on hard pack?” but, “Should I be skiing a Helldorado on hard pack?” (No disrespect intended for the Helldo, which we much admire.)

Before I dismount my soapbox, it should be said that the great savant of the fat ski, Shane McConkey, didn’t imagine skiers trying to ski a Spatula or Pontoon the same way Stenmark dissected a GS racecourse. His espousal of a reverse-sidecut shape wouldn’t imperil the knee as long as it was deployed properly. Which is a long way of saying, if the design doesn’t encourage or require a high edge angle to perform as intended, and the snow surface is soft enough to allow the rider to surf in lieu of edging, then the vulnerability red light is off, although it’s still incumbent on the pilot to steer the ship.

Is there a limit to how wide skis will become? Mercifully, yes, there is a biomechanical limit determined by how far apart one can place one’s feet and still remain upright. It’s not easy to ski in the stance personified by Yosemite Sam, wide enough to slide a horse between your thighs without the saddle brushing against Gore-Tex. When your feet have to be wider apart than your shoulders, you’ve gone about as fat as you can go.