Skis have two primary exterior systems—bases and edges—which fulfill two primary functions:

Bases are like pressure distribution devices that take the weight of the skier and distribute it over the snow so that they reduce friction and allow the skier to slide smoothly over the snow.

Edges are like rudders that cut through the snow in such a way that it changes the hurtling skier’s line of travel. They’re what make you turn when you’re doing it right.

Skis perform these basic functions in a variety of ways, depending on footprint, baseline, construction and tuning.

Baseline

A ski’s baseline is defined by how it rests on a horizontal plane, as viewed from the side. Most skis made in the 20th century had an arched baseline, with the ski contacting a flat surface only at points somewhere near the tip and tail. This upward arch is called camber, a term still in use, although the cambered area of a ski may no longer extend from tip to tail.

Most skis now being manufactured with waist widths over 80mm end the cambered area somewhere in the forebody of the ski and deflect the rest of the ski forward of this point upward, so it won’t contact the flat plane.

This feature, often referred to as “rocker” or “early rise,” improves the ski’s propensity for riding over whatever terrain feature it encounters, thereby expanding the variety of terrain in which the ski will perform well.

Skis over 100mm underfoot often elevate, or rocker, the tail as well so the fatter ski will pivot more easily. Tip and Tail rocker includes at least a smidgeon of camber underfoot; Full rocker skis are flat or even reverse cambered underfoot.

The trade-off is the rockered tail doesn’t provide the same degree of support when loaded and has a tendency to smear, rather than carve, the end of a turn. This “smear-ability” can be complemented with a turned-up, twin-tip tail, although it’s possible to rocker the tail but keep it otherwise flat, for greater buoyancy along the full length of the ski.

Footprint

By “footprint,” we mean a ski’s overall shape and surface area. A key geometric measurement is the ski’s sidecut, or how its width varies along a given length.

Modern skis are called “shaped” skis because their relatively deep sidecuts create an hourglass shape that the previous generations of skis didn’t have. The degree of sidecut will contribute significantly to how the ski wants to turn.

Tip Waist Tail

The wider the tip is relative to the waist, the tighter the initial arc of the turn will be, and the more “automatically” the ski will pull into the turn once tipped on edge.

The wider the waist, the easier it is to balance on the ski, slide the ski sideways (or skid) and the more the ski will tend to float in powder. The narrower the waist, the more rapidly the ski can roll from edge to edge for quick direction change.

The wider the tail is relative to the waist the more the ski will try to finish a turn by itself, steering across the fall line. The narrower the tail is relative to the tip, the easier the ski will release the turn as the skier eases up on the edge pressure at the end of the turn. Up to a point, a narrower tail gives the skier more control over turn completion.

The tip/waist/tail measurements — along with its length — reveal much about a ski’s intended purpose. The waist width plays such an important role in defining what a ski does best that it is often used to define the technical boundaries between ski categories. For example, “All-Mountain West” skis are generally regarded as belonging to a family with waist widths hovering between 95mm and 100mm.

Traditionally, a ski’s sidecut could be defined by just the 3 tip/waist/tail measurements, but increasingly designers are fiddling with new dimensions. Skis with five distinct contact points are now commonplace, creating tip and tail sections that aren’t part of the sidecut underfoot that determine the ski’s potential carving properties.

Construction

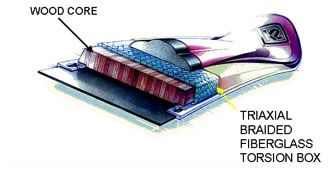

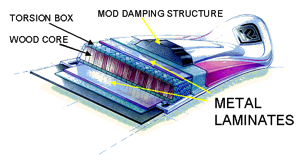

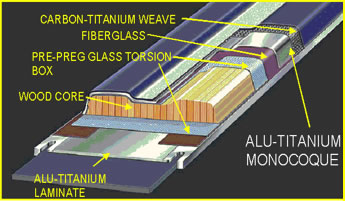

There are lots of ways to build a ski, and over time just about all of them have been tried. At this stage in the evolution of ski design, there are three major design concepts—torsion box, laminate and monocoque— each of which can be combined with one or both of the other. For example, a torsion box may be wrapped with a bottom laminate of metal, and capped with a top layer of metal that extends down to the edge to create a metal monocoque.

Torsion Box: Fiberglass is woven or wrapped entirely around the ski core. Materials other than fiberglass may be present in the weave, and additional laminates maybe applied either inside or outside the box. Wrapping the core in one (or more) boxes creates a strong frame with a lively response to pressure.

Materials

Wood

In the beginning, skis were made of wood and wood remains the most common choice for ski core material because it’s abundant, relatively cheap and has known physical properties. In order to improve skiing’s image as a green industry, some ski makers are using more readily renewable woods in their core lay-ups.

Foam: In the world of skis, there are two very different kinds of foam used in ski cores.

-

-

- Injected polyurethane (PU) cores are cheap to make and very lightweight. They are used mostly in junior skis, where their structural weakness is less important than low cost.

- Milled foam cores, often made from acrylic foam, are not cheap. Milled foam cores are more uniform and lighter than wood, which allows for a thicker, more torsion-resistant core without increasing weight.

-

Fiberglass

Fiberglass is the most common structural component used in ski making because it’s very versatile, relatively cheap, has high tensile strength and keeps its molded shape over time.

Titanium Alloy

The metal commonly referred to as “Titanium” is almost entirely aluminum, with a few other alloys (zinc, magnesium, copper and titanium) mixed in. Titanal™ is a brand name used by a common source for this alloy, and is often (mistakenly) used as a synomyn for the material. Titanium laminates are often only .4mm thick, so longitudinally they’re as soft as overcooked spaghetti, but once molded into a ski, they create a torsionally stiff beam. Almost any ski built for speed has Ti laminates in it, and may use different thicknesses here and there to achieve the desired behavior.

Titanium alloy helps to dampen harmful vibrations at speed, while still allowing the ski to maintain the slight vibration needed for optimal glide. Titanium laminates are the most expensive component in a ski, so manufacturers are always looking for a cheaper substitute, such as carbon fiber or basalt, to play the same role. The search continues.

High-Tech Fibers

Many of the high tech fibers used in ski manufacture come courtesy of the aerospace industry Their amazing strength-to-weight ratios are ideally suited for skis. At one time or another, ski makers have used Boron, Kevlar, Twaron, ceramic fiber, graphite, carbon and even blended them with metal fibers to selectively strengthen and dampen the ski.

The latest addition to the materials stockpile will be a hard one to trump in that it is one atom thick and has the highest strength-to-weight this side of science fiction. This miracle substance, Graphene™, is carbon in its most elemental form, one atom thick. Head currently owns the exclusive rights to use it in skis.

Polyethylene

All ski bases are made of polyethylene (PE), either with or without carbon or graphite additives, which makes the material softer (and black) but also greasier and therefore faster in most snow conditions.

The Holy Grail of Flex

For a ski to carve a turn on its edge and hold its line, a few things have to happen:

- The ski must be tipped up on edge. If it stays flat on the snow, the ski’s sidecut never comes into play.

- The skier has to be able to bend or counter-flex it lengthwise. If the ski doesn’t counter-flex, the edge won’t make continuous contact with the snow and the sidecut can’t do its job of changing the ski’s direction.

- The ski edge has to grip the snow securely, so the ski must be torsionally stiff enough to resist twisting as the ski is pressured during the turn.

One of the never-ending quests of ski design is to create a ski that’s soft lengthwise so it’s easy to bow into an arc yet stiff laterally so the edge grips securely. Every ski design addresses this problem one way or another.

The perception of a ski’s flexibility is directly related to how camber is deployed (or not) along its baseline Full-length camber works in conjunction with flex to help create even pressure distribution along the ski.

The Dope on Damping

Shock absorption or damping is a big deal in ski design because skis are constantly buffeted by terrain as they glide across the snow. The faster the skier goes, the bigger the jolts to the ski and the harder it is to keep the ski down on the snow. This is why all high-end skis have some kind of speed management technology built into their design.

Every ski maker has its own special way of dealing with shock, but all damping systems, regardless of the technology used, work by converting the shock wave running down the ski into some other type of energy. Some systems also put the shock energy to use performing some other helpful task, such as pressing the ski extremities back on the snow or stiffening the ski to improve edge grip.

A simple analogy: damping systems in skis are like shock absorbers and suspension systems in automobiles. Inexpensive cars with little in the way of suspension systems handle very differently from luxury cars that buffer road vibrations and smooth out the ride.

The Paramount Importance of Tuning

Base and edge finish are crucial to how a ski performs. A brilliantly designed ski will not function properly if the base isn’t flat, structured and waxed and the edge isn’t properly finished. We’re not going to deliver a tuning clinic here, but skiers should know that manufacturers have invested millions of dollars in base and edge finishing machinery to deliver a ski with a flat, structured base and a precisely ground, polished edge.

But—and it’s a monster “but”—every factory tune should be presumed guilty of some flaw or flaws unless close inspection proves its innocence. Machines can have problems trying to negotiate today’s rollercoaster baselines, and factory pre-set edge angles may not be optimal.

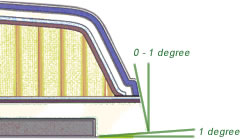

Most manufacturers finish their edges with 1° of base bevel and 1° of side bevel (see diagram), whereas many good skiers have found they prefer to increase the side bevel to 2°. The higher the degree of side bevel, the better the ski will hold at extreme edge angles, but technical accuracy becomes more critical and high bevel angles are difficult to maintain.

While you don’t need to learn how to tune your own skis to race-room standards, learning how to wax the bases and touch up the edges should be part of any serious skier’s skill set. For once your precious new skis hit the snow—not to mention the ski rack on top of the car—the wonderful factory finish starts to degrade. As the finish declines, so will the ski’s performance. To perform their best, skis need regular—ideally, daily—maintenance performed on base and edges.

Performance : The Big Picture

- How a ski performs is the result of a complex matrix of materials and how they are assembled (the design recipe and the ingredients), combined with the other components of the ski-boot-binding-interface system.

- No one single ingredient or component determines the behavior of the whole, but all contribute to the performance of the whole.

Alpine Ski Categories *

The easiest way to subdivide the world of Alpine skis into genres that allows for a fair comparison across brand boundaries is to segregate them by waist width and the corresponding terrain where such a silhouette is best applied. Using this method, the vast majority of the ski world can be categorized as follows:

Category Waist Best Terrain

Technical 65mm – 74mm 100% Groomed, ice to corduroy

Frontside 75mm – 84mm 80/20 Groomed/Off-Piste

All Mountain East 85mm – 94mm 75/25 Groomed/Off-Piste

All Mountain West 95mm – 100mm 60/40 Off-Piste/Groomed

Big Mountain 101mm – 113mm 80/20 Off-Piste/Groomed

Powder > 113mm 100% Off-Piste

There are also a few specialty genres with avid adherents, among them, notably, twin-tipped Pipe & Park models. Such special-use models are not the focus of realskiers.com. We primarily serve those skiers who prefer going downhill while facing their direction of travel after having ridden some conveyance to the top. In this vein, we recommend without reservation the expertise of Jason Borro and skimo.co for those hardy souls who cherish self-powered backcountry skiing.

Non-FIS Race

Volkl Racetiger Speedwall SL UVO

The finest skis in the world are made for alpine racing. The vast majority of skiers who have never kicked out of a start house would be amazed by how many different race models are re-made every year by every brand participating on the World Cup. They are all wildly unsuitable for recreational skiers. The organization that sanctions international racing, FIS, sets strict limits on ski shape and standheight in an attempt to level the playing field and ostensibly improve skier safety. FIS regulations have made the modern GS ski – once the preferred everyday ski of experts – all but unskiable by anyone without World Cup level skills.

Fortunately for those elite skiers who can handle the power of a race ski, every manufacturer who makes FIS-sanctioned skis also makes slightly softer versions with more forgiving dimensions. Generically categorized as Non-FIS Race models, they are also know as “beer league” or “citizen race” skis. They are the best skis made that are available to the general skiing public.

Technical

Technical skis borrow heavily from race ski technology and some are even intended for running gates but most are meant for high speed cruising without the bother of setting courses and tracking times. As the name implies, these skis aren’t for unskilled skiers but for those who instinctively ride at high edge angles. If you want to ski very fast and in control on gem-hard surfaces, these are the sticks you want on your feet.

Because Technical skis are specifically crafted for Power skiers, we rank them solely according to their Power rating. We report their Finesse scores, but they don’t factor into the hierarchy of our results. If you’re looking for slow-speed performance and a measure of off-trail versatility you’re fishing in the wrong pond.

Frontside

Head Supershape i.Titan

This category (75mm-84mm) encompasses the broadest range of skier abilities, from the never-ever to the fall-line charger. Almost every entry-level ski for the neophyte falls into this family, but there are also a lot of choices for skiers who prefer to fly at around 50 mph. The intended terrain is almost exclusively groomed, but the wider bodies within this family will travel off-slope if asked. Because carving turns is the aspirational activity associated with skiing on groomed trails, this genre is sometimes tagged with the “Technical” label, but we prefer the term “Frontside” as it embraces a wider scope of both terrain and abilities.

The majority of skis in this genre are sold with an integrated binding that is inextricably married to a specific model. While the binding company is responsible for the binding design, it’s up to the ski maker to come up with an interface that will secure it to the ski. The integrity of this linkage may vary from brand to brand, but the idea behind the so-called “system ski” does not: the binding sets in or on an interface that adds damping, reduces the binding’s natural impingement on ski flex and increases the skier’s leverage over the edge.

All-Mountain East

Rossignol Experience 88 HD

The “East” modifier is meant to imply that this narrower collection (85mm-94mm) of All-Mountain skis is a match for skiers who go on groomed trails most of the time but want the freedom to foray into the untamed backside of the mountain when conditions merit. The cream of this crop have settled on a waist width of 88mm or 90mm underfoot, creating a very versatile profile that qualifies for the “All-Mountain” moniker. Some brands differentiate their “88” from their “98” (All-Mountain West) model by making the former in a less burly construction that will slip into a slightly lower price point. They make excellent “re-entry” skis for consumers who have been out of the ski market for several years.

All-Mountain West

Blizzard Bonafide

If there is a single, do-it-all ski—particularly for western, big-mountain skiing—it no doubt lives in this category and probably has a waist width of 98mm. The reason is simple: up to this girth (95mm-100mm), these relatively wide skis don’t feel fat underfoot, so they ride the groom like a Frontside ski yet provide as much flotation in powder as possible without the width being a negative when the powder is gone. Manufacturers recognize the importance of this genre and therefore give it their very best effort, creating a rich array of options for the high performance skier. It’s remarkable that one category can contain so many different sensations and almost every ski is really, really good. Pay attention to this category, Dear Reader, for if you don’t already own an All-Mountain West ski, you will.

Big Mountain

Salomon QST 106

It wouldn’t be unfair to lump all skis over 100mm at the waist into a giant bucket labeled, “Powder,” and leave it at that. Obviously, the fatter the ski the better the flotation, so pick a ski based on how high you want to ride on new snow and you’re good to go. We decided to divide the powder pie in two because there are big behavioral differences between the Big Mountain bundle of skis (101mm-113mm) and the cluster over 120mm. The best of the Big Mountain brotherhood are everyday skis for strong riders on—you guessed it—big mountains where the snow is reliably deep and soft. But there are also easy riders in this corral, skis that will help the less talented whip their powder skills into shape.

Powder

K2 Pinnacle 118

The fattest of the fatties (>113mm) are true specialty sticks, meant for when the snow is so deep even a 108mm won’t float high enough. This reality won’t keep some folks from sporting them every day, but this is lunatic-fringe behavior, as hauling a barge around on hard snow is no picnic for the knee joint. If you live in the west it makes sense to own a Powder board as a second pair; if they’re you’re only pair of skis, we hope you also own a helicopter. Even though the performance of these skis depends largely on their shape and surface area, there are still large behavioral differences among models. One particular divide occurs along the carve/smear schism, models that still retain a preference for a directional, arced turn versus rides that want to pivot and slide sideways down the hill.

Pipe & Park

Line Blend

We could call this genre “twin-tips,” as every Pipe & Park ski has to have this feature, except designers have also appended turned-up tails on every other chassis they could lay their hands on. Still, the half-pipe and terrain park are where twin tips were spawned and their proper domain. The constructions tend to be basic in order to keep down both weight and cost. (Also, P&P skis are most likely to be returned to the manufacturer on a warranty claim—“I can’t imagine how it happened; I was just skiing along…”—but that’s another story.) P&P skis are made with spin moves in mind and must be tolerant of landings that are less than perfect, criteria that hold little appeal to the non-aerialist.

Women’s Skis

Head Total Joy

Once a solitary, stand-alone category focused on intermediates, women’s skis now come in nearly every footprint available to men. Often made in the same mold as their parallel unisex models, women’s models aim to serve the same aspirations as a man buying in the same category. They are generally lighter weight, always softer flexing, may have a slightly more forward mounting position and invariably flash a fem cosmetic.

Junior and Children’s

Junior skis come in two basic categories: expensive and cheap. The pricier models imitate the constructions and cosmetics of similar adult models, be they All-Mountain, Big Mountain or Race.

- Junior: Junior versions are always modified from the adult version (a little or a lot) so the lightweight junior skier can flex them in lengths over 120cm.

- Children’s: The least expensive junior skis are not based on adult designs. They use PU-injected cores that are supple enough for lightweight skiers to bend and come in lengths below 140cm.

For the child just starting out, any ski will do. As the child improves, it makes sense to step up to a stouter construction, tailored to the same terrain preferences that apply to adults. In general it’s safe to assume that adolescents weighing more than 130 pounds should start looking at the shorter lengths of adult models rather than the longest lengths in junior models.

Size Matters

Since shaped skis first appeared about 20 years ago, skis have been gradually shrinking in length. Why the history lesson on length? Because the past is where you come from, and some of you, who haven’t bought a new ski in ten years, find yourself in a brave new world where all the skis have shrunk. Now more than ever, finding the right size ski—rather than the right brand or model—could be the most important part of the ski buying decision.

Longer skis make longer turns. Shorter skis make shorter turns. Shorter skis are easier to steer. Longer skis create more contact with the snow. In general, lighter people belong on shorter skis; heavier people belong on longer skis, as a ski’s first job is displacing its rider’s weight.

The safest route to proper size selection is to consult the manufacturer’s literature. In the absence of any other guidelines, try this. For most types of skis, put adult men on a ski around 180cm long. For women, consider something around 160cm to be average. When in doubt, go shorter for a Frontside ski, longer for a Big Mountain ski. For heavier or more aggressive skiers who like speed, go up a length. For lighter or more cautious skiers who prefer control, go down a length.

For kids, the best guideline is to go chin height for beginners. Depending on the model, more skilled junior skiers should go to nose height, or as long as head-high for advanced kids. As with adults, it’s usually best to err on the short side, which makes chin-to-nose height the best choice for most juniors.