This series of articles was written in the fall of 2015 and reflects the technology available at the time. It has since been updated in 10 Revelations devoted exclusively to women’s skis. Links to these essays are ensconced at the end of this article. Some of this content has moved behind the paywall, so to see all the archived info you need to be a subscriber to Realskiers.com: still only $24.95 for newbies, $19.95 for recurring members. – JH

Back Story

Allow us to peel back the veil of time to an epoch 20 years ago. Fat, powder-specific skis were just finding a following on the fringe of the sport and carving skis, still unknown in the New World, were too new to have a name yet. The only skis marketed as made for women were entry-level recreational skis built in unisex molds. In other words, women’s models were spin-offs of the cheapest recipes from the men’s menu, often made even worse by deleting a few parts to lighten the structure and earn an “L” designation.

Location, Location, Location

Returning (just for a moment) to those hoary years of yore, before anyone thought two seconds about making a women’s ski, all that could then be done in the name of adaptation was move the female skier’s mounting point forward on a ski patently, defiantly made by men for men. The apostle of the doctrine of a forward mounting point, as lonely as Diogenes searching for an honest man, was Hall of Fame member Jeannie Thoren, who faced derisive opposition every step of the way.

Bear in mind, this was before shaped skis made it seem inadvisable to hop-scotch all over the ski in search of the perfect balance point. Even after shaped skis were so dominant that the adjective became unnecessary, moving the mounting mark forward – relative to where it would be on another ski from the same mold, marketed for a man – became a shibboleth of women’s ski manufacture that endures to the present day.

Only when the manufacturer decides to cut new molds (for every size) for a new women’s model can the sidecut’s mid-point move, instead of just the mark. To the credit of those who simply move the mounting mark (or provide a potpourri of marks, as is the wont today), those who start from scratch also end up moving a woman’s midpoint a centimeter or two forward of where they would have positioned it for a man.

No brand has thought more about this issue than K2. (Sorry, we love you Head, Völkl and Atomic, but K2 has been doing empirically derived women’s positioning studies since Biblical times.) The conclusion their engineers have reached is that women feel greater comfort and control 2cm further forward on the same length platform as men, so they build sidecut, baseline and flex response around that point.

Over in Mittersill, Austria, the engineers at Blizzard see women’s skis differently. All their current [2015] women’s skis issue from unisex molds; the only concessions to the probable presence of a female aboard are a switch to Paulownia and bamboo in lieu of beech or poplar to lighten the core and a recommended mounting point nudged forward by a centimeter. The reason for the slight shift forward isn’t intended as a form of ladies’ aid, but an adjustment for the likelihood that the female skier’s boot will be shorter, with proportionately more material in front of the skier’s balance point. All Blizzard is trying to do is put a woman more precisely where a man would be on the same ski.

Blizzard’s Viva series of Frontside skis for women are system skis (the norm in this groomed-snow genre), which allow the skier to tinker with stance position to her heart’s content. Blizzard’s IQ system uses only a single, central screw to attach its integrated Marker binding to the ski, so it bends easier under light pressure and weighs less, both benefits for the smaller pilot.

To create its line of Freeride women’s skis, Blizzard slips what amounts to a backcountry core into a unisex mold, screens multiple mounting points over a feminized topskin and−ta-da!−another woman’s ski is born. This somewhat facile approach hasn’t dampened sales, as the Black Pearl was, by some measures, the best-selling women’s ski in the specialty retail channel in 2014. Even though Blizzard’s “a goose is just a lighter gander” approach is working, the pressure to innovate in a viciously competitive market may push them to present alternative solutions for women in the near future.

What Do Women Want?

Blizzard is by no means the only brand to blur the boundary between a men’s backcountry model and a “made-for-women” model. Dynastar’s Cham High Mountain and Cham W skis are indistinguishable under the hood. Rossignol takes advantage of the already lightweight construction of their best-selling 7 series to clone a parallel set of women’s models, all unadulterated. Salomon uses the same molds for many, but not all, of their flat women’s skis and the same lightweight cores are used for both men and women, a trend to lighter constructions that crosses the gender divide.

Völkl has a split personality when it comes to women’s models, sometimes treating women with special consideration and other times overlooking whatever distinctions may exist between the sexes. The most important new model in their women’s line this season, the re-vamped Aura, is an example of the latter attitude. It’s essentially the new men’s Mantra, right down to its mounting marks, with a little lighter core. By the way, our testers loved the Aura, rating it first in its genre, so it didn’t turn out too burly or unmanageable despite being essentially a man’s ski.

When it comes to building their Frontside women’s skis, Völkl changes their tune, adopting an all-women-all-the-time approach. When they created their Essenza series before the 09/10 season, Völkl began with a blank canvas and re-imagined the women’s ski. They called the combination of features they created Biologic®, bringing flex, stance and geometry into harmony with a woman’s physiology.

While Biologic has been updated over the years to incorporate a touch of tip rocker and the xtraLight core created for the V-Werks series, the female-specific aspects of the series remain intact: an adapted stance, geometry and flex.

By elevating the ski’s profile under the integrated Marker toe piece, Biologic levels the female skier’s stance so she’ll stand taller, with less quad strain and a reduced tendency to drop the hips rearward. By widening the tip and thinning the tail, the Biologic forebody pulls the skier into the turn on a tight radius while the tail releases it. This increases control at the top of the turn and reduces potential knee strain as the ski crosses the hill. The Biologic flex complements the sidecut and neutral stance by being firmer in the forebody so the wide tip can engage quickly and softer underfoot and through the tail, for easy bending and release of the turn.

Like Völkl, Atomic also looks at the women’s ski market from two opposite perspectives, split along much the same line, but arriving at quite different adaptations. While not above adopting a unisex mold to develop a women’s (Vantage) series, Atomic also makes a couple of women’s Frontside collections that they cooked up from scratch. Atomic collaborated with the University of Salzburg on a study of performance attributes specific to women which led to the development of the Cloud and Affinity series. Aside from the universal imperative to reduce weight wherever possible, these skis incorporate 3 specific features that make them more user-friendly for women.

One, they increase the angle underfoot by building a 2mm ramp in the mounting area to slightly re-position the hips forward without lowering them (which would drive weight rearward, precisely what the slight ramp angle is designed to suppress). The Salzburg study showed that 2mm of elevation under the heel helped women to ski better, faster. Two, these models use a V-shaped sidecut, reducing the flare in the tail so it releases the turn more readily and thus is less likely to induce adverse loads on a woman’s more vulnerable knees. Three, they tweak the core profile to create a more compliant tip and tail so the flex overall feels softer and smoother.

Like almost all brands, Atomic fiddles around with core composition to make their women’s models lighter, using select grades of poplar in some instances and no wood at all in others. The use of pre-impregnated materials also trims weight as they minimize the amount of glue ladled over the core.

Material Matters

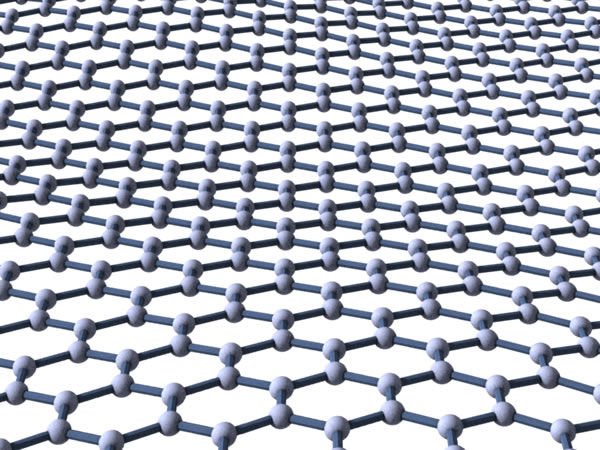

An atom’s-eye view of Graphene, a latticework of carbon one atom thick.

The ambition to create a lighter ski that still lays rails on hard snow at high speed has been an objective of ski design for decades. Throughout its brief history, the technical evolution of the modern alpine ski has depended on the development of materials created for other, better-funded industries, most notably aerospace. Aircraft-grade aluminum, fiberglass, Kevlar, piezo-electronics and carbon fiber, just to name a few, once-exotic materials, have all been adopted by ski developers in the service of creating a better vibration-managing, directional sliding device.

All these innovative materials allowed the ski designer to make a ski lighter and stronger. The most versatile material in the lighter-and-stronger toolbox is carbon, usually in a fiber form that can be woven into fiberglass or otherwise integrated into the ski construction, adding strength with relatively little mass.

The quest to optimize carbon seems to have reached its apogee with the arrival of Graphene™, carbon delivered in atomic-level doses. Added to the resin that’s essential to all fiberglass elements, Graphene delivers strength 300 times that of steel in the least amount of mass imaginable. Wherever Graphene goes, other, heavier materials can be excised, allowing the ski designer to redistribute weight (and flex resistance) along the ski.

The first application of Graphene in skis debuted in the 2015 season with the Head Joy series, 6 new women-specific models. The elimination of bulkier materials gives the low-profile Joy skis remarkable sensitivity to the snow and a supple, sinuous flow. The narrower models (Pure Joy, Total Joy) destined for hardpack conditions use Graphene to reduce weight in the mid-section, distributing relatively more weight to tip and tail for better edge contact at speed. The wide-bodied Big Joy and Great Joy deploy more Graphene at the extremities so these skis are easier to pivot and surf.

As they started with a fresh template for each Joy model, Head had a free hand in mid-point positioning. They began with the same progressive sidecut radius used in their terrific ERA 3.0 designs and let their women’s test team determine the optimum binding position based on their on-snow experience. Head also dropped the camber line on the Joy series so it transitions to the forebody rocker more smoothly, creating an overall mellower ride.

Graphene isn’t the only material you’ve never heard of being used to improve the performance and/or reduce the weight of women’s skis. Texalium is aluminum-coated fiberglass used in the RoX dampening matrix on some K2 women’s models. Why Texalium? Because K2’s female testers preferred it to the carbon-reinforced RoX used on the men’s models, which is reason enough in our book.

Koroyd is a honeycomb structure strong enough to serve as a core material either by itself (usually at the tip and tail, as in Salomon’s Rocker2 models) or in conjunction with other materials (as Head has done in their GKC sandwich cap construction). Rossi’s success with their see-through, honeycomb Air Tip design will likely result in more Koroyd coming to a ski rack near you.

What’s in a Name?

Before women’s skis populated every category but the true race genre, manufacturers made it easy to identify their handful of women-specific models by appending a “W” or “L” to the unisex model name of the ski from which they were cloned. Today’s women’s skis tend to come in families, with each family member having a first name and a family name, such as Affinity Sky. The only major brand to still cling to the W tag is Dynastar; the last remaining L is at Kästle, where it stands for Light, not Lady.

The case of Kästle is curious enough to merit a sentence or two. Kästle doesn’t catalog their LX 82 or LX 72 as women’s skis, but they do more to feminize their construction than many brands that overtly court the fairer sex. They switch from a square-sidewalled torsion box to a cap/sandwich construction, in the process thinning out the core profile. Unlike any other ski with an L in its name, the LX’s have two sheets of titanal in the mix, so they’re still strong skis; they just bend more easily under gentle pressure.

The highest concentration of all-female families is found in the Frontside genre, where the intended user is presumed to spend most of her time on groomed terrain. The Frontside arena is the native soil of the system ski, meaning skis in this genre are mated in some fashion with a binding. The marriage of the two components almost always entails an interface of some sort, presenting an opportunity to toy with how the skier is balanced on the ski. But aside from striving to keep the interfaces low and light, no brand has seen fit to exploit the ski/binding interface as a means of adapting a woman’s stance.

The development of women’s specific skis in all the wider genres (All-Mountain East, All-Mountain West, Big Mountain and Powder) will be given a boost by the boom in backcountry interest, as both segments are driven by the quest for the Lightweight Grail.

The only significant segment that seems immune to the appeal of weight loss is the Race genre, where lightweight is associated with adjectives like nervous, flimsy and deadly. The unsponsored female racer won’t find an L or W next to her SL or GS ski; she’ll simply be handed a shorter length from the men’s collection. However, should a young woman prove talented enough to compete at the highest level, her skis will still look like the men’s, but beneath the skin they’ll be tailored to her to a T.

Such is the ironic state of affairs in the wacky world of women’s skis that models presented as made for women may be technically indistinguishable from a men’s backcountry board, while an elite woman’s race ski is painted to look like a man’s but is actually the most adapted women’s model made.

Why Cinderella’s Slipper Doesn’t Fit

Seriously? A size 6 foot in a size 9 boot?

Even to the non-skier, the idea of a woman’s ski boot makes sense. Women have their own shoe sizes, don’t they? There must be something about a woman’s foot that’s fundamentally different from a man’s, and since fit is so important in ski boots, surely it follows that a woman’s boot should be specially lasted for women.

And so they are, up to a point. Except in the race category, about which we’ll chat shortly, every boot with the moxie to call itself made for a woman adds padding around the ankle and Achilles area, an accommodation for the fact that the female foot is proportionately lower volume in this area than a man’s. For most boot makers, that’s it for morphological modifications to the last of the liner and lower shell.

Two other areas get special treatment, the upper cuff and the materials used in the inner boot. The upper cuff on a woman’s boot is invariably lower than a man’s for the simple reason that women tend to be shorter. This is the one and only concession made in the world of race boots, where men and women are otherwise dealing from the same deck. On recreational boots, the woman’s lower cuff may also be scalloped in the back to relieve pressure on the calf.

The one feat that has to be accomplished at the point of sale is getting the boot on and closed. You can’t fit (or ski) in a boot you can’t close, so some extra effort goes into making cuffs that can grow in diameter either mechanically or by heat-assisted expansion.

Women tend to have poorer circulation than men, so they may get an insulation upgrade over what the corresponding men’s liner offers. Women also have a different idea of what connotes comfort, which has inspired a menagerie of faux-fur linings, some of which are clearly meant to re-assure the non-skier that she may enjoy some aspects of the ski experience after all.

We’ve just covered the entire spectrum of modifications built into made-for-women ski boots. Didn’t take long, did it, even for someone as prolix as yours truly?

This is not to say there aren’t unisex features that work marvelously for women, only that such special features aren’t unique to women’s boots. Let’s take a snapshot of three such features that are generally more beneficial for women than they are for men.

One of the best boot designs for the recreational skier in recent memory, the Atomic Hawx, contains hidden in its bones a feature Atomic never promotes and may not even be aware of. In both its men’s and women’s iterations, the area over the first cuneiform bone is domed, forming a natural haven for this common protuberance in the female mid-foot. This isn’t such an easy area for a bootfitter to modify and as noted above, there’s only one lower shell made from scratch for a woman and this isn’t an area touched by its adaptation.

As readers of this monograph are increasingly aware, not many products in the ski world are made from the ground up for women. Given this foundation, total adaptability (without compromising structural integrity) would seem to be a game-changing capacity, and so it has proven to be.

Salomon commercialized heat-moldable panels in the lower shell of their high-end boots several seasons ago, a technology that’s evolved to include every shell component but the sole and steering column. True, it’s not women-specific, it’s skier-specific irrespective of gender, but it attends to any and every female foot anomaly as accurately as it can be done without also making an injected custom inner boot and custom insole. (We’ll return to this insole business in a bit.)

In the four-buckle boot, achieving a tight wrap in the cuff is critical to control and fit. Women have a tough time cranking their boots down because it’s difficult to get enough leverage. Head created the Double Power buckle over a decade ago, and it’s still the best built-in leverage booster ever concocted. A spring-loaded latch flips out on demand to give a gal (or guy) 50% more closing force. Maybe some day, when we all have personalized jet packs, we’ll also all get Double Power buckles on our boots.

One feature we don’t see anymore on women’s boots is an elevated heel position, although a couple of brands do make inserts that plug into the zeppa (boot board) to elevate the heel and snug the heel pocket. Since men’s boots have been dropping in forward inclination over the last several seasons, women have also seen their heels lowered. In theory, this helps women achieve a more upright stance with consequently less quad strain, lower incidence of knee sprain and greater edging power at the end of a carved turn.

But what happens when a theory developed around not just men’s needs, but elite men’s needs, is applied to a lower shell that is then handed over to recreational women, unchanged? Every manufacturer acknowledges in their design that the women’s calf will be lower by changing the upper cuff geometry, but assume women’s ankles–the critical joint for skiing–will be positioned just fine in a men’s lower shell.

There’s compelling evidence that this isn’t the case. When product development authority David Bertoni was international marketing manager for Salomon bindings in the mid-90’s, he conducted a wide-ranging study of ramp angle, known in binding engineering circles as delta. The particular ramp angle he examined wasn’t created by raising the heel in the boot but by adding shims between the ski and binding. The study showed that among men there were very different needs and desires for less or more ramp angle depending on the skier’s activity/arena. Mogul skiers, for example, had to have more ramp angle for their event; it didn’t matter if the heel position compromised edging at the bottom of the turn because most mogul skiers never finish a turn. Downhill racers had exactly the opposite requirement; without a lower heel to apply pressure past the turn apex, racers don’t finish the course, period. Recreational men were somewhere in between, making the overall picture complicated.

The women’s results were so different from men’s that Bertoni recalls he found them “startling.” Every woman in the study, from Olympian to terminal intermediate, felt more comfort and control when raised 5mm to 15mm higher in the heel. While Bertoni’s delta study didn’t examine increasing heel elevation in the boot, he believes that any change in the angle of the foot relative to the ski, however it’s accomplished, will reposition a woman’s center of mass forward, towards the ball of the foot. If the increase in heel height is effected inside the boot, it will have the multiple benefits of raising the calf slightly out of the boot, increasing leverage over the tongue and raising the ankle relative to the cuff pivot, all of which help the woman achieve a comfortable, balanced athletic position. Bertoni compares it to the body positioning a point guard assumes when an opponent with the ball is bearing down, on the balls of the feet, ready to go in any direction.

Pressed to further illuminate what was meant by “comfort and control,” Bertoni expounded. “In the end, it’s a balance issue. The women felt stronger and more agile because they were in a better, balanced position. The reason is, by raising the woman’s heel relative to the ski she achieves a mechanical advantage over the boot she doesn’t have in the lower position.”

One possible stance “correction” Bertoni counsels against is increasing the forward lean angle of the upper cuff. “The more you increase forward inclination, the more the butt drops and weight shifts rearward,” he notes, or exactly the opposite of the intended effect.

Bertoni’s confidence in his study’s findings was reinforced when he checked in on the Race Department technicians who serviced Salomon’s race stable. He found that the top field hands were making the same modifications in the racers’ boots–normally around 5mm of lift–that his binding study suggested was the sweet spot for a woman’s stance. In the case of the racers, more “comfort and control” translated into the only word that matters in racing: faster.

Bertoni also worked in boot R&D at Salomon, so he’s aware of the pitfalls of making absolute statements about ski boots and how to fit them, but there’s one point on which he’s adamant: “99% of the public is over-booted in terms of stiffness and with women the problem is compounded because, compared to men of similar abilities, they ski with greater precision at slower speeds and so can’t generate the force required to budge a cold, stiff ski boot.”

Bertoni overstates the percentage of skiers whose boots are too burly, but his observation about women’s boots is spot-on. Skiing requires a range of motion (R.O.M.) at the ankle; a woman positioned too low in a boot that’s too stiff to begin with has no chance of ever feeling comfortable on her skis.

The current chorus of boot product managers in the US—all of whom peddle women’s boots with low ramp angles—uniformly sings the same song and their brands take no stance on the increased ramp angle issue but leave it instead to the specialty retailer to sort out on a case-by-case basis.

Would that most of America’s bootfitters were so savvy. Sad to say, while there are a few truly great boot fitters in this country, many know just enough to be dangerous. Trusting them all to accurately gauge the need to retrofit the ramp angle on each women’s boot they sell is unfettered optimism.

The ski trade could use more women with boot-fitting skills

Photo courtesy of MasterFit University

Seek Professional Help

We’d love to tell our female readers that all they need to do is fashion 5mm of some dense foam and stuff it under their heels and increased comfort and control will be theirs. However, it turns out the heel and the instep are connected and when you raise one you elevate the other. Women already have a tendency to possess more prominent bones in the mid-foot, so pressing their insteps up against a rigid plastic shell is uncomfortable at best. This is why the Universe created experienced bootfitters.

As a former boot product manager, I recognize the dangers of making across-the-board changes to a commercially successful boot design on the assumption that the new widget will work for everyone. For example, the one area of women’s boots that gets the most attention is the calf, where all manner of gizmos exist to expand the cuff aperture. The forgotten woman in all this fun is the one with a slender, tapered calf who ends up having to stuff whatever boot she gets with anything she can find to help stabilize her now hypermobile lower leg.

The fact is every foot, regardless of gender, is unique and presents its own problems inside a ski boot, the most complex piece of footwear you will ever own. There are other factors, such as kinesthetic awareness and athleticism, which are as important to consider as gender when it comes to boot model selection. A good bootfitter isn’t just trying to equalize pressure around the foot so it feels good; he or she is adapting a piece of critical equipment to a skier with particular traits and ambitions. At a minimum, stance and underfoot support must be addressed alongside “fit.”

I don’t want to get our readers all misty-eyed, but mankind really is a field of wildflowers. We’re all different, and our feet, in particular, are all over the place. This is why boot fitters (and boot designers) can’t be too rigorous in their belief systems about what benefits such-and-such a skier. If we at realskiers were to insist on any First Principles, they would be that the skier’s foot should be supported and the ankle must have an accessible range of motion. We don’t believe every skier in the world needs custom insoles, but the world would be a slightly better place if they had them, or at least decent trim-to-fit insoles. The same could be said for injectable custom inner boots, but we’re not holding our collective breath waiting for this sea change in behavior to materialize.

The one undisputed, inescapable difference between male and female is the latter lives with a lower center of mass (COM). Most stance adjustments, whether built into the ski, the binding ramp angle, an adapted sidecut, binding positioning and/or boot heel height, are attempts to address this change in balance point.

A balanced stance is the foundation, literally and figuratively, upon which confidence is built. This doesn’t mean every woman will automatically ski better with more ramp angle beneath her. What it does suggest is that a great many skiers, whether male or female, could benefit from professional analysis of their gear in general and how it affects stance in particular.

In our experience, accurate self-assessment of stance position and optimum boot functionality is difficult for trained technicians and all but impossible for the layman.

Therefore, our advice to female readers is to schedule a rendezvous with the best bootfitter at your local specialty ski shop, ideally during a tranquil moment in the fall. Bring in your current skis and boots, wear shorts and don’t forget your thinnest pair of ski socks. An experienced bootfitter can analyze the functionality of your set-up and advise you on a recommended course of action to put you in a more balanced position on your skis.

Epilog

The Europe-based ski and boot manufacturing community has a long history of paying lip service to the special needs of woman skiers. For years the prevailing attitude about making women’s skis was that the problem took care of itself: the shorter unisex lengths women would buy automatically make a shorter radius turn. Problem solved!

Bertoni’s previously-described delta study, general biomechanics and informed intuition all point to something we probably should have mentioned at the outset: men and women are different.

As the made-for-women market has become more commercially important, more of the major manufacturers are devoting more resources to women’s products. K2 and Head both invested heavily in women-specific gear for 2015, a move we hope our readers support with their wallets.

If there’s one take-away we hope you’ve gleaned from this little treatise, it’s this: if you’re even thinking about buying a ski boot online, for man, woman or child, stop. We don’t care what you think you know, you don’t know enough to do this.

Trust us on this one. We’re on your side.

Further Revelations on the U.S. women’s market:

https://realskiers.com/revelations/the-wacky-world-of-womens-equipment-2/

https://realskiers.com/revelations/best-womens-skis-201617/

https://realskiers.com/revelations/womans-world-part/

https://realskiers.com/revelations/womans-world-part-ii/

https://realskiers.com/revelations/womans-world-part-iii/

https://realskiers.com/revelations/the-state-of-the-womens-ski-market/

https://realskiers.com/revelations/the-state-of-the-womens-ski-market-ii/

https://realskiers.com/revelations/realskiers-2021-womens-ski-test-a-series-of-linked-recoveries/

https://realskiers.com/revelations/the-best-womens-skis-of-2020/

https://realskiers.com/revelations/the-2021-22-womens-ski-market-2/