For decades, retailers, rental shops and ski distributors have supplied the secondary market with their used and/or unsold inventory. While there will continue to be a robust secondary market, where the gear that stocks them comes from and how it’s distributed could change dramatically in the near future.

I attended my first Labor Day ski sale in 1972, at Gart Bros.’ downtown Denver location. A bustling throng of rabid skiers occupied every square inch of the multi-level store and spilled out into the street. I had seen pictures in National Geographic of religious gatherings on the banks of the Ganges that rivaled what I was witnessing, but I never thought I’d see a similar sea of humanity in a sporting goods store. In early September, no less, months before any Colorado ski area would accumulate enough natural snow to open.

Once I was in the store, the veneer of dispassionate observation was immediately shelved, replaced by an overwhelming desire to make it out alive. I was there, like many of my skiing brethren, to bottom-feed, to find a new ski at a price I could afford, which ended up being around 100 bucks. The only hint to its origins was the word “FISCHER” in letters as tall as the ski was wide, emblazoned on the forebody and tail. I couldn’t have cared less what use it was intended for; it was a pair of skis that appeared to be in one piece and their acquisition got me one step closer to trying out for the Copper Mountain Ski School.

The Gart Bros. SNIAGRAB sale (“Bargains” spelled backwards!) created a template for a fall sales event that would in time be copied by practically every ski shop in America: gather up as much distressed gear as you can find, slap a hefty discount on it and watch it run out the door. Around the same time that Labor Day sales became a fixture on the ski calendar, the ski market was loaded with low-end package options. Every chain with any buying clout created its own ski/binding combos. It was a golden age for the price-conscious consumer.

To give you an idea of the importance of the secondary market to those who knew how to exploit it, when I was at Salomon during the 1980’s we manufactured “close-outs” in order to dominate the world of ski swaps and pre-season sales. (The earlier you can get a sales staff trained in how to sell your product, the greater the likelihood they’ll continue to champion your brand deep into the season.) “Labor Day” sales became so popular, some shops began theirs in August and others didn’t wean themselves off steeply discounted gear until October.

The market conditions of today are nearly the polar opposite. (See, Flipping the Pyramid.) At least two layers of entry-level price points have simply evaporated, along with the channels to market they once ruled. At the other end of the price spectrum, manufacturers keep coming up with new genres that carry a premium price tag. (See the entire world of backcountry gear.) But while the winds of change have gutted the low end of the retail business, the price-conscious skier has always found refuge and relief in the secondary market.

The phenomenal success of Sniagrab and other pioneer Labor Day sales depended in large part on being situated among Denver’s dense skier population, coupled with Gart’s willingness to load up on distressed inventory anywhere they found it. It was a given that Gart’s long-time rival, Cook’s, would immediately go toe-to-toe with Gart’s Labor Day promotion, and it wasn’t long before every entity with a skiing connection got in on the game. Boutique resort shops, film festivals, regional ski shows, local ski teams and other charity cases all dipped their beaks into the pre-season sale waters. Also interwoven into the secondary market was a robust circuit of stand-alone swaps, nurtured by a network of scavengers who culled their inventory from disparate retailers, rental shops and ski suppliers.

By this point in the narrative, my perspicacious Dear Readers can’t help but wonder, “Where does all this secondary market inventory come from?” In a word, mistakes. No retailer can order so accurately that they sell down to the last stick, so a certain amount of ugly-duckling leftovers is inevitable (and in a way, desirable) among the brick-and-mortar retail community. When a single-storefront retailer over-orders from a few ski brands, or even when one sector of the country endures a no-snow year, the impact on the overall market is short-lived. But when year after year practically every major ski brand misses its forecasts by a country mile, the tide of product overwhelms the normal channels’ ability to absorb it.

The current ski market dynamics are the result of the pandemic and the 50% surge it injected in what had been a fairly stable sales volume. This artificial inflation created lofty forecasts that persisted well after the surge in sales began to abate. Practically overnight, suppliers came to the realization that they had seriously missed their projections. As was the case back at the dawn of Sniagrab, suppliers looked to their largest accounts to absorb the excess, which used to mean brick-and-mortar chain stores, but today’s mega-accounts are all online discounters.

I’ll leave it for another day to discuss the wisdom of selling one’s best models at rock-bottom prices to your most predatory accounts, and instead try to provide a snapshot of what’s happening with the most visible entities on the Internet. Curated.com, that touted a huge number of skis and boots sold through its pipeline, is gone (and good riddance). Once dominant players such as backcountry.com and Level 9 are sliding in and out of bankruptcy; no matter the fate of these institutions, their inventory has to end up somewhere, and it’s bound to amount to a lot of units earmarked for long discounts. Part of this tsunami of unsold equipment will re-appear at fall ski swaps, and another chunk will find its way to other online opportunists that will flog them all season long.

Vail’s network and Ikon’s partners are now engaged in massive demo programs that will generate thousands of used skis destined for some sector of the secondary market. So there will be a steady supply of discounted skis that may end up at your local ski swap, but it’s also possible the area conglomerates will chose to liquidate this avalanche of used gear via their rental outlets. This means the secondary market is unlikely to run out of used gear to unload, but the supply of new skis available at fire-sale prices will gradually peter out simply because suppliers are now forecasting more accurately. Once the current oversupply is exhausted – and assuming the thrice-burned supplier community forecasts more conservatively – the pipeline of new skis at high discounts should narrow to a trickle.

As I pen this pensée in the late spring of 2025 (slated for publication just prior to – you guessed it – Labor Day), the ski trade in America is anxiously trying to peek over the horizon to see which way the tariff winds will be blowing next year. It’s looking like this idiotic policy won’t have a buzz-killing effect on equipment prices this winter, but all bets are off when it comes to forecasting for the 26/27 season.

While I’m not privy to any insider information, I believe next year we’ll see significant price hikes driven by a combination of impending tariffs and the uncertainty surrounding their fluctuation. Fears of a full-blown recession will keep ordering in check on both the wholesale and retail level. If my sources are correct, this year’s pre-season sales could be your last best chance to get a great deal on new skis. But thanks to the Ikon and Epic demo fleet turnover, the supply of used skis looks to be inexhaustible.

Related Articles

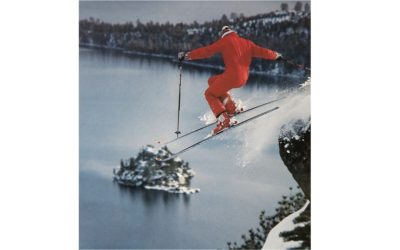

Larry Prosor belongs in the U.S. Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame

Larry Prosor didn’t just document the birth of extreme skiing in America, he ignited it. The spark was lit by a nine-page barrage of eye-popping images lovingly displayed in the pages of Powder...

On Beyond Stöckli

Twenty-five years ago, even astute ski industry insiders wouldn’t have predicted that tiny Swiss brand Stöckli would one day be the darling of the specialty retail channel. Then as now, Stöckli’s...

Mining the Revelations Archives

When I first raised the topic of composing a weekly newsletter with Realskiers.com founder Peter Keelty, he coughed, bit down on the Salem that was forever dangling from his lips and curtly advised...