I realize I’m swimming against the tide.

The American skier has considered his abundant options and chosen some form of an All-Mountain model as his everyday ride. (Pardon me, ladies, much of what I’m about to assert doesn’t apply to you, as American women tend to coalesce around the low end of the “All-Mountain” spectrum.) No one with an above-average skill set should have any trouble navigating all manner of in-bounds conditions on one of today’s premier all-terrain models. Why nit-pick about a system that’s working just fine?

I’ll tell you why. There are a couple of hidden traps in the All-Mountain ski/skier relationship, one stemming from a skier shortcoming, the other inherent in the ski. One characteristic of damn near every All-Mountain model – in Realskiers’ parlance, a ski with a waist width of at least 85mm but not more than 100mm – is a double-rockered baseline. The ski designer can try to mask this deficiency in any number of clever ways, but there’s no getting around the fact that there is less ski-to-snow contact than with a fully cambered ski. So, why the universally double-rockered baseline? It is, of course, to mask the technical deficiencies of the typical pilot. A double-rockered baseline presents a far shorter – and far more forgiving – platform to the terrain underfoot, making off-trail conditions easier to ski for those who don’t ski for a living.

The latent deficiency the skier brings to the party is a tendency to smear some phase of every turn, a bad habit that becomes easily engrained on manicured slopes, particularly on an All-Mountain ski that isn’t predisposed to latching onto the top of a carved turn. Permit me to dwell for a paragraph or two on a technical detail that illuminates the difference between a carved turn as executed on a buffed-out groomer versus the truncated turn the same advanced skier applies off-trail.

To illustrate my point, imagine a full, semi-circular carved turn, with the skier beginning to tilt the ski on edge the moment the tips cross the fall-line. Let’s call this action, “entering the turn through the front door.” This technique creates the cleanest arcs on groomed slopes, but it doesn’t travel that well off-trail, where the need to dodge trees, skirt cliff bands and negotiate tight lines is far more important than maintaining edge contact. In the hodge-podge of off-piste conditions, the skier often has to drift sideways to the edge, a move I refer to “entering through the side door.” The need to slide laterally before engaging the edge is one of the main reasons expert skiers gravitate to wider all-terrain skis as their everyday ride. (Improved lateral lubricity is also why I use a modified thumbprint base grind, but that’s grist for another Revelation.)

The issue this pensée is meant to illuminate occurs when the lazy edging habits engrained from countless forays off-trail are transferred to crowded, six-lane groomers. One of the benefits of a skier population trained to make complete, round turns is that the movements of your fellow travelers are much more predictable. Simply put, the mountain is a safer place the more it is populated by skiers with sound technical skills. So, it stands to reason that the general skiing population would be better off if more of us would choose a narrower ski that optimizes edging control rather than a wide ski that encourages aimless drifting.

I know, I’m a dreamer. The main reason Americans haven’t adopted Euro-style, two-footed carving technique is because it requires a bit of work, perhaps even some coaching and training. Not that I’m advocating for a nation of super-carvers, all locked into their private trajectory tunnels, but I do pray that the skiing public will aspire to ski under control, and that involves learning when and how to get on and off one’s edges. To properly learn the skill, it helps to have a ski that is on the same page, which is why I’m recommending that you adopt one of the following four Frontside models as your next ski. You’ll still be able to ski the whole mountain, I assure you, but you’ll wring so much more sheer pleasure out of your groomer laps that you’ll end up having more fun, more of the time.

In compiling this short list of Frontside favorites, I prioritized models that reside on the border between Power and Finesse properties, amazing skis that combine sublime stability with dazzling responsiveness. For a complete overview of the 2025 Frontside genre, please visit https://realskiers.com/2024-mens-frontside-skis/. Links to the individual model reviews on Realskiers.com are included in the brief, behavioral snapshots provided here.

American skiers have been conditioned to think that a true all-terrain ski has to be at least 90mm underfoot, with an amply rockered baseline. Skinnier skis are fine for manicured groomers, but as soon as the surface devolves into a disheveled mess, it’s time to climb on a broader board. The new Völkl Peregrine 82 makes a strong case that the best Frontside skis shouldn’t be confined to the tireless tedium of carving up corduroy; they can handle whatever the backside of the mountain has to dish out.

There are two on-snow traits that elevate the Peregrine 82 from the rest of the field: one is rebound energy and the other is the turn shape versatility inherent in its 3D Radius Sidecut, which essentially harbors a short-radius capability inside a long-radius chassis. The only thing the Peregrine 82 can’t do is float through knee-deep powder. Big deal; any ski over 100mm underfoot can fill that bill. Finding a ski that will do everything else at an elite level is relatively rare.

If you come from a race background, your favorite Supershape is likely to be the e-Speed or e-Magnum, but if you’re accustomed to a fairly wide all-mountain model, you’ll probably gravitate to the e-Titan. The common misconception that one needs 100mm’s underfoot to tackle off-piste terrain won’t survive contact with the e-Titan. Particularly when the off-trail goods are best in the trees or other tight quarters, a ski with a talent for tidy turns has all the versatility you need to subdue the untamed side of the mountain.

The 2025 e-Titan lops 4mm off its forward contact point and loses 2mm at the tail, tamping down the carve-insistent personality of its forebears. The e-Titan is still very much a carving ski at heart, but now it’s programed to be more open-minded about turn shape. It provides a consistently stable platform that wraps into the top of a mid-radius turn, holds an edge with a python’s smooth insistence, and concludes with a burst of rebound energy that converts the exit of every arc into an effortless stroll in the park.

The MX84’s connection to the snow begins in the shovel, where its new Hollowtech Evo design upgrades its shock absorption effect with extra layers of dampening agents, so the tip stays welded to the snow. This isn’t just an advantage on groomers, where the shovel finds early engagement on hard snow, but in bumps, as well. Hollowtech Evo helps calm the turbulence in tight troughs and maintain snow connection on the backside of every bump. Skiing moguls is transformed from a brutal mugging to feeling like your skis are just following gravity’s flow.

The 2024 MX83 was a very good ski; the 2025 MX84 is a great one, right there with the Stöckli Montero AR as a speed-loving, corner-hugging, crud-eating machine. You’d think the MX84 was made to be an all-condition ski until you roll it out onto a long, undulating carpet of corduroy, where it can display its electric talent for carving. No matter what tune you play in your head while you ski, the MX84 can dance to it.

When Blizzard completely overhauled its All-Mountain collection this year, the Brahma 82 had already carved out a spot for the Anomaly 84. Having learned from the Brahma experience to keep the performance standard high, the Anomaly 84 uses the same FluxForm construction as its three beefier brethren. Even though the Anomaly 84 is manifestly the tightest turner in its family, it’s still a long-turn lover at heart. It is also perforce the quickest Anomaly edge-to-edge, although tiny, C-shaped carves aren’t naturally in its repertoire.

The Anomaly 84 feels right at home motoring along on well-compacted boulevards, despite a baseline that begs to be taken off-road. What the Anomaly 84 provides is an on-trail ski that isn’t fixated on short turns, buried edges and slingshot exits. Its off-trail DNA is always available to draw on if you care to dabble in the crud at the edge of the trail, but it doesn’t need new snow to calm it down or give it a sense of purpose.

Related Articles

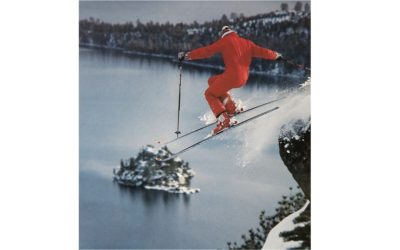

Larry Prosor belongs in the U.S. Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame

Larry Prosor didn’t just document the birth of extreme skiing in America, he ignited it. The spark was lit by a nine-page barrage of eye-popping images lovingly displayed in the pages of Powder...

On Beyond Stöckli

Twenty-five years ago, even astute ski industry insiders wouldn’t have predicted that tiny Swiss brand Stöckli would one day be the darling of the specialty retail channel. Then as now, Stöckli’s...

Mining the Revelations Archives

When I first raised the topic of composing a weekly newsletter with Realskiers.com founder Peter Keelty, he coughed, bit down on the Salem that was forever dangling from his lips and curtly advised...